Stephen Rowley

2012 (Roland Emmerich, 2009)

In his book Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, Mike Davis notes the particular enthusiasm in popular culture for destroying Los Angeles, and categorises the different ways in which the city bites the dust. Nuclear weapons lead the way with 49 surveyed works. Earthquakes: 28 works. Invasion: 10. Monsters: 10. Pollution: 7. Gangs or terrorism: 6. Floods: 6. Plagues: 6… and so on. What nobody, so far, had seen fit to do was just tip Los Angeles over and throw it in the ocean.

Enter Roland Emmerich.

Well, I’ve dived into the world of Twitter. My original intent was just to create another option to alert people to my infrequent updates, but I ended up using the site frequently. You can find me here. My main account will include stuff about both my main online interests (film and urban planning) as well as my various other obsessions.

As to my impressions of Twitter itself after a couple of weeks of using it – well, its a strange beast. Obviously, given I’ve taken it up with some regularity, I understand the appeal. Basically, it’s not so much a social networking site as a kind of rest-stop for tired bloggers (this is why the description of it as a micro-blogging site is much more accurate than lumping it in with things like Facebook or MySpace as a social networking site). Certainly the 140 character limit on posts seems liberating compared to the drudgery of maintaining a webpage or blog. When audiences expect sites to update with new content at least daily, that’s a huge demand on the author; 140 characters allows for the faster turnover without the chore factor. Twitter is basically reducing our expectations of on-line content so that they better align with expectations about how fast sites should update.

Spotted over at MaryAnn Johanson’s site, and too clever not to share – Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1950s style. It’s not quite as good as Raiders of the Lost Ark as made by a bunch of kids, but it’s still pretty cool. And certainly better than Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Dogs in Space (Richard Lowenstein, 1986) and

Dogs in Space (Richard Lowenstein, 1986) and

We’re Livin’ on Dog Food (Richard Lowenstein, 2009) and

He Died With a Felafel in His Hand (Richard Lowenstein, 2001)

Movies are time capsules. Inner city suburbs of Melbourne such as Fitzroy, Brunswick, Carlton, Richmond, St. Kilda and Collingwood are now largely gentrified, filled with young professionals and with only a modicum of their former grunginess preserved; much of the shabbiness that remains – pokey cafes, tatty pubs – is artfully preserved to maintain an inner city chic. Yet the older, scruffier inner Melbourne is still there in all its glory in films like The Club, Malcolm, Death in Brunswick and Monkey Grip. Amongst this group, no film stands as deliberately as a time capsule of a place and an era as Richard Lowenstein’s cult classic Dogs in Space, from 1986, which has now been released on DVD after playing at the 2009 Melbourne International Film Festival.

The film chronicles life in a Richmond share house in the late 1970s, centering on the spaced-out musician Sam (Michael Hutchence) and his easygoing girlfriend Anna (Saskia Post). Virtually plotless, it depicts the parties and conflicts in and around the house as various different subcultures (punks, hippies, and one unfortunate uni student) co-exist. Many of the housemates are in underground punk bands, and the film was inspired by real-life events in the Melbourne post-punk music scene. As Lowenstein’s subsequent documentary We’re Livin’ on Dog Food (which also played at the festival and which is included on the Dogs in Space DVD) makes clear, the timing of Dogs in Space was at once far enough away from the real events that it already had a nostalgic air, and yet close enough that the film could get a documentary-like feel through the participation of some of the real people and bands.

It’s nice to see Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are getting some love (see here) and opening well (see here). I posted the trailer for the film back in May and remain feverish in my anticipation. (It opens in Australia at the start of December). It’s not just that I admire both the book, and Spike Jonze, it’s also that the trailer gave the distinct impression – now also being supported by some of the reviews – that Sendak has approached this not so much as a kids film but as an all-ages film that is about about childhood. That’s a really interesting and rewarding avenue that isn’t explored often enough, presumably because studio bosses think it is likely to confuse people about whether the film is for kids or adults. (Never mind that one of the most commercially successful films ever made is exactly such a film). The reviews (even some of the less positive ones) give me increased hope that it was timidity, not real problems with the material, that caused the studio to delay the release of the film for so long.

I won’t post the link to the wonderful second trailer, since that’s in all the Australian cinemas right now. Instead, here’s some test footage of an aborted Disney adaptation directed back in 1983 by none other than future Pixar supremo John Lasseter. The footage itself is nothing special – a kind of show-offy exploration of how computers would allow animation to more freely play with depth – but it’s an interesting glimpse at an intriguing mix of artistic sensibilities. I have a lot of regard for Lasseter, and for good Disney, but you have to wonder whether the studio was in any creative state to deal with a masterpiece like Sendak’s book in 1983.

A few years ago I wrote a long appreciation of the film critic Pauline Kael (you can find it here). The discussion of Kael herself was bracketed by some thoughts about the state of the practice of film criticism. I started with the following thoughts:

…criticism isn’t held in high esteem because it is seen as a by-product of art, rather than an expressive pursuit in itself. There is some justice in this, as even the best critics are there to serve the appreciation of the medium they are talking about, making it difficult to justify the consideration of their criticism as a piece of creative work with its own worth. As a result, critics are held in contempt by many, and writing about or discussing the quality of a critic’s work in any depth can be seen as a self-defeating exercise. What could be more of a redundant exercise than criticising critics, and thus putting yourself a level even further down in the hierarchy? To the extent they are thought about at all, then, critics tend to be seen as the bottom feeders of the artistic establishment. The general quality of film criticism has done little to change this perception: many media outlets take the view that basically anyone can review a movie, meaning that even the professional film reviewing sector has a very poor base standard. While the public’s interest in cinema ensures an audience for film criticism, most readers undoubtedly feel that if they were given the job they could write as good or better reviews themselves, and frequently they would be right.

I finished with this:

It’s perhaps easier to appreciate Kael now that she’s gone, and fifteen years have passed since her retirement with nobody of her stature emerging in the field since. Critics have only become more devalued in the interim. Kael’s 1963 suggestion that there were “so few critics, so many poets” seems a little quaint now: in the age of the internet, anyone can be a critic, and there sometimes seem to be more people offering reviews than there are readers for them. And while some of this writing is very good – the internet allows long-form and niche writing that for the most part can’t be achieved in traditional media – the landscape of criticism is so fractured that no voice can gain the kind of cultural purchase Kael achieved. Such diversity of opinion is generally a good thing, but what film criticism as a field has lost in this process is a universally recognised beacon of excellence. The defining critic of the last decade is probably Harry Knowles, from the website Ain’t It Cool, who became the heavy hitter of a generation of self-taught internet critics and whose style (a combination of incoherency and sheer geekish mania) has unfortunately become the defining model for internet criticism. Voices such as Knowles have their place, but if criticism is to be seen as playing a vital role in film culture, both critics and their readers need to demand a higher standard: “real bursting creativity” rather than mediocrity. This requires an appreciation for the defining figures in the field, and Kael – for all her infuriating flaws – remains the gold standard against whom other critics should be judged.

Generally little has changed since those comments (although Knowles seems to have faded into the background as a critical voice on his own site; this is actually a change for the better since many of Ain’t It Cool’s other contributors are substantially better writers than Knowles). With occasional rare exceptions – one notable example being a long feature Erin Free did in FilmInk back in December 2007 – critics remain reluctant to publicly examine what they do or to praise good work in their field. There is basically no recognition of excellence for critics. When a society of actors give out awards, they give out awards for acting; when a society of directors give out awards, they recognise directing; but critics’ associations give awards to those in other professions. This is all well and good – obviously film critics’ main game should be to recognise excellence in filmmaking – but along the way critics have forgotten to recognise achievements in their own field. This doesn’t help to foster a rise in standards of film criticism.

The arrest of Roman Polanski on the outstanding warrant for the 1977 charges of unlawful intercourse with a minor has brought new attention to an aspect of the directors’ life that many still find murky. It will also no doubt revive interest in Marina Zenovich’s Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, the documentary on Polanski that played at the Melbourne International Film Festival last year (which I reviewed here). With some reservations – explained in my review – I recommend the documentary for those who are finding the complex history of Polanski’s charge, trial and exodus confusing.

What I find both interesting and disturbing is, as I noted in that review, the extent to which Polanski has been rehabilitated into public life. These are, after all, very serious child sex charges, and normally our society would see nothing as more unforgivable. There are some mild mitigating factors, but nothing that comes even close to excusing what Polanski – even by his own account – did. Yet somehow excuses seem to be made for Polanski, to the point where we need articles like Kate Harding’s outraged reminder that Polanski raped a child to bring the focus back on the original crime.

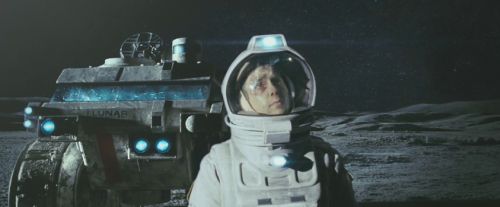

Moon (Duncan Jones, 2009)

As I suggested back in 2007, when reviewing Danny Boyle’s Sunshine, anyone trying to make an old-school intellectually-driven “hard” science fiction film faces a battle against both familiarity and economics. Familiarity, in that the key works in the genre (2001, Solaris, Silent Running, Dark Star, and so on) have mined so much of the territory available against the genre that it can be hard for newcomers to find new creative territory. And economics, in that those who finance such movies struggle with the constraint that in order to afford the special effects their plots require, they may get pushed to include action and spectacle that is at odds with the more cerebral thrust of their story. Boyle struggled gallantly with both constraints without quite prevailing over them, but now we have Duncan Jones’ Moon to demonstrate decisively that it is still possible to make smart, original science fiction that isn’t intimidated by history.

Originally published as an editorial under a joint by-line with Tim Westcott and Gilda Di Vincenzo in Planning News 35, no. 8 (September 2009): 4.

Originally published as an editorial under a joint by-line with Tim Westcott and Gilda Di Vincenzo in Planning News 35, no. 8 (September 2009): 4.

Have we allowed sustainability to become a boring topic? Is it increasingly tempting to flick past the articles in Planning News and elsewhere that stress the urgency of action on climate change with nothing more than a quick “yep, know that” shrug?

If you can relate to this guilty impulse, we have a problem. Sustainability ought to be our core business as planners. The primary rationale for having a planning profession is surely because in some situations the market, left to its own devices, can lead to bad outcomes: is there a better example of this than environmental degradation? (Indeed it is, quite literally, the textbook example: remember the “tragedy of the commons?”) There surely can’t be a bigger challenge for this and the next generation of planners than ensuring more sustainable communities. Anecdotally, an urge to help plan a more ecologically sound built environment is central to the reasons many of our keen young planners enter the profession.