There’s something slighty perverse about getting excited by the fact that a paragraph of introductory text from a movie has been released. (I don’t think it happened with Blade Runner or Gladiator). But when it’s Revenge of the Sith… Well, I’m afraid I can’t control myself. The opening crawl is now up at www.starwars.com, and goes like this:

Film

How good does the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy movie sound?

This is a book beloved by geeks everywhere: Hitchhikers is one of those franchises like Monty Python, Star Trek, and Star Wars, that attracted the nerdy and friendless like moths to the flame. The first two novels (The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Restaurant at the End of the Universe) also happen to be amongst the great comic novels of the last half-century. While Restaurant is a little disheveled, narratively speaking, the first novel has a perfectly rounded story that would be perfect for a film. The only obvious difficulty would seem to be one of selection: what to put in, and what to leave out. Because it originated as a radio play, the whole script is sitting there right before you as you read (in contrast to the way that Adams’ later books became increasingly internalised, and therefore all but unfilmable).

Sideways (Alexander Payne, 2004)

Alexander Payne’s Sideways is a small, impeccably done character study that may just get crushed under the expectations that are surrounding it. It arrives in Australia swathed in Oscar and Golden Globes buzz, and with strong reviews from some notable critics (such as David Stratton’s 5 star rave on At the Movies). Inflated hopes are the enemy of a movie such as this: while a blockbuster action picture’s sheer mass gives it some resistance to hype, a picture as slight as Sideways can be left seeming diminished if the experience is anything less than transcendent. I was left slightly underwhelmed by Sideways, which is a shame, because the film itself did nothing wrong: it’s pretty much note-perfect, and deserves to be assessed without the burden of Awards hopes. While I’m sure Alexander Payne won’t want to send his Golden Globe for Best Picture back – the award was given while I was writing this review – but it may be that the film itself would have been more comfortable quietly finding its audience.

The Incredibles (Brad Bird, 2004)

Brad Bird’s The Incredibles is the latest in the extraordinary winning streak of the Pixar animation studio, but it is also a film that challenges everything we thought we knew about Pixar films. In their first five features (Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc, and Finding Nemo) a house style emerged based largely on the sensibilities of John Lasseter, director or co-director of three of those five films, and generally we know what to expect from the studio. Their features are unashamedly kids’ films, albeit ones rich enough to entertain all ages. They use non-human characters (toys, insects, monsters, fish) for their central cast. They centre on a pair of “buddy” heroes (Woody and Buzz, Sulley and Mike, Marlin and Dory), or a troupe of friends who all work together. The tone – warm, gently sentimental, and without cynicism – strongly recalls the best of the early Disney animated films. This consistency in approach surely derives from the use of in-house directorial talent, with the directors other than Lasseter (Lee Unkrich, Pete Doctor and Andrew Stanton) having learnt the ropes working alongside Lasseter.

12 Angry Men (Sidney Lumet, 1957)

Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men is a permanent trace of an impermanent form: the live television anthology show. In the early fifties, the US networks produced several anthology programs in which new original dramatic plays would be performed live to air. By their nature these programs were destined to fade from memory: the form had been replaced by more conventional filmed (ie not live) dramas by the end of the fifties, and few of the programs were preserved. Yet they retain a fascination for those, like myself, who never saw them. Live anthology programs challenge the post-fifties conception of what the television medium is about: instead of being a poor cousin of cinema (which, despite all the great TV out there, is what I think most of us still subconsciously accept TV as), these shows took much of the best of live theatre and cinema to create a unique hybrid medium. The anthology shows attracted talented writers and created genuinely prestige programs. The Best Picture winner for 1956, Marty, was based on a Paddy Chayefsky-scripted episode of Philco’s Television Playhouse, while 12 Angry Men, an adaptation of a 1954 episode of Studio One, was nominated for the same award in 1958. Try to imagine an episode from even the best of today’s television shows being adapted into an Oscar winning film only a few years after airing on television and you’ll have an idea of how far TV has fallen in the cultural stakes. No wonder Hollywood feared it.

Dr No (Terence Young, 1962)

Dr No (Terence Young, 1962)

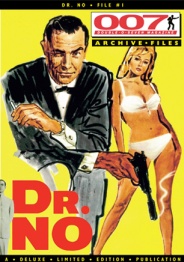

(Note: This review started out as part one of a planned seven-part essay on the 1960s Bond films, consisting of an essay on each film and a seventh part that would explore Bond’s journey since the 1960s. That project became so overwhelming that I have had to move onto other things, but I thought the first part would be of interest. It was republished in the 007 Magazine Archive Files, pictured at right, in May 2011.)

It’s hard to watch Dr No and not see it as the start of something. This isn’t just a product of hindsight – the popularity of the Bond novels meant the film was understood as the first of a series even on its initial release. As a result, it is usually discussed more as a template than a movie. Analysis of it tends to either emphasise those aspects of the film that foreshadow the series to come, or those aspects of this first entry that appear aberrant in light of the later entries. Such an approach is valid, and I won’t avoid it either. Yet Dr No, paradoxically, works as the originator of a series because it stands so well on its own. It was in the sixties that the best Bond movies were film classics in their own right.

Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004)

One of the reasons that Bowling for Columbine, Michael Moore’s study of the American gun culture, was so wildly successful was that for the most part it renounced the faults of his other work. Columbine was a thoughtful, complex film that avoided the oversimplifications or falsehoods that tended to blemish his earlier films and books. It deservedly catapulted Moore into the public awareness after years as a fringe figure known mainly to left wing political observers, documentary fans, and media buffs. With this new attention coming to Moore during the extremely conservative presidency of George W. Bush, it should not be surprising that Moore would attempt to use his new popularity to launch a concerted attack on the US president. The danger was always that in the resulting film, Fahrenheit 9/11, Moore’s hubris and overzealousness would cause him to lapse back into old habits.

Shrek 2 (Andrew Adamson, 2004)

Every so often, when the accolades and box office seem to overrate the merits of a film, I find myself suffering a backlash against a movie despite having liked it. For example, Dreamworks / PDI’s original Shrek was a slick, fast, funny film, and I enjoyed it immensely, but from some of the reviews of it, you’d think nobody had made a send-up of fairy tales or Disney movies before. Shrek was, of course, far from the first such movie: it is the latest in a very long counter-Disney tradition that goes back at least to Tex Avery. And despite the reflexive assumption that the Disney studio could never make such a film, it came only the year after Disney’s manic The Emperor’s New Groove, a film I think is superior as a straight-out comedy. Indeed, there are many recent animated films I would rate above Shrek: the aforementioned Groove, most of Pixar’s films, The Iron Giant, even PDI’s earlier film Antz.

The Day After Tomorrow (Roland Emmerich, 2004)

One of the principles I try to hold to when reviewing films is to avoid simply savaging a film. The smugness of smart-arsed critics who can do nothing but pick apart a movie always irritates me. Which isn’t to say that bad movies shouldn’t be criticised. It’s just that the best reviews of bad films are those that also stop to note the good points amongst the bad. Likewise, most classic films have their share of flaws, and defining why these films succeed despite their problems is often difficult. Critics need to appreciate the elusiveness of the strange alchemy that makes a good film. As they say, nobody sets out to make a bad movie.

Nobody, that is, except Roland Emmerich.

Kill Bill: Volume II (Quentin Tarantino, 2004)

When I reviewed the first part of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, I concluded with a rhetorical question: would anyone have enjoyed just the first half of Once Upon a Time in the West? My point was that it was difficult to assess Volume 1 prior to the release of Volume 2, since it was bound to end up as an empty exercise in style if it could never reach any conclusion. Sergio Leone’s classic sprung to mind as an example of a perfectly rounded film by a master of film technique that wouldn’t amount to anything if you showed just part of it. Having seen Volume 2 of Kill Bill, however, I can see that the example was all wrong. Once Upon a Time in the West is a film with purity of purpose that stands as a supremely executed single entity. Kill Bill, by contrast, makes perfect sense as two movies. Not only is each volume an anthology, constructed out of a series of episodes that add up to a larger whole, but each volume is starkly different in overall purpose and tone. I’m now convinced Tarantino intended for the film to be split in half all along, and I’m not one of those who hankers for Tarantino’s promised single movie version (I can see it being schizophrenic and unsatisfying, like From Dusk Till Dawn).