Yearly Archives: 2009

One of the most dispiriting things about day-to-day statutory planning is the paper warfare. Consultant planners prepare a report justifying their proposal; given the length and repetitiveness of planning schemes, that might be twenty or more pages long. Council officers then prepare their own assessment, but for various reasons they tend not to rely a great deal on the applicant’s report. Apart form the description of the proposal – the bit that applicants know a Council planner will always read – many consultants’ reports are not especially useful as the starting point for Council’s assessment. I suspect most planners will know the kind of report I mean: huge slabs of text cut and pasted from the scheme; permit triggers incorrect, incomplete, or scattered through the text; glib and formulaic non-responses to the real issues of merit; and so on.

There’s a cycle here, in that the less Council officers rely on application reports, the more sketchily they are done, reinforcing the tendency of local government planners to give them fleeting attention. Meanwhile, Councils have traditionally tried to encourage better documentation through the issuing of extensive application checklists listing every last thing to think about. This increases regulatory burden, and further reinforces the trend towards over-documented but under-thought applications. And when Council officers finally come to assess the application, they largely start from scratch, duplicating work that in many cases has been – or should have been – done by the permit applicant. The whole process sees a lot of paper exchanged, but too little communication and co-operation between Council and consultant planners in getting applications across the line.

W. (Oliver Stone, 2008)

Oliver Stone’s W. is a solid dramatisation of George W. Bush’s life, but Stone has conditioned us to expect something that is both flashier and more incendiary. At his best Stone is an exceptional filmmaker – his earlier political drama JFK is one of the best films of the 1990s, whatever you might think of its central thesis – and with his reputation for shooting from the hip there is no doubt many expected W. to be an extended polemic. Instead, the film is traditionally constructed and fairly measured in its tone. Judging from some of the reviews, which have generally been lukewarm, Stone might have overestimated the willingness of the public to accept a fair-minded account.

I have seen some characterise the film as almost a defence of Bush. I don’t think that’s the case; some of the reviews seem to have set up a false dichotomy between “balanced” and “anti-Bush,” and suggested that because Stone’s film is the former, it can’t be the latter. But Bush is the kind of figure about whom a fair account can still be scathing. Stone is far from defensive of Bush, but he does humanise him and mostly avoids cheap shots. Why take cheap shots when the big picture provides such a compelling condemnation?

Originally published as an editorial under a joint by-line with Tim Westcott and Gilda Di Vincenzo in Planning News 35, no. 2 (March 2009): 4.

Originally published as an editorial under a joint by-line with Tim Westcott and Gilda Di Vincenzo in Planning News 35, no. 2 (March 2009): 4.

The big planning challenge for the government this year is to get runs on the board. Disenchantment normally advances slowly, like old age, but the release of Melbourne @ 5 Million (M@5M) late last year will likely be remembered as a defining moment in which disillusionment made a bold and striking advance. Neither the Minister nor Melbourne 2030 are new any more, and if we are to maintain our faith in both, 2009 needs to see less spin by the government, more honest acknowledgement of problems, and more tangible progress towards planning goals. We are too far into the life of Melbourne 2030 to still be polishing our implementation measures.

Star Wars: Where Science Meets Imagination (Powerhouse Museum, 4 December 2008 – 26 April 2009)

Film fans might not feel that much reluctance to admit to being Star Wars fans any more, but museums obviously still feel a cultural cringe. So, for example, when an exhibition of models, props and costumes from Star Wars tours, there has to be some kind of legitimising excuse. A decade ago there was an exhibition (which I saw at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C.) which was based on the links between Star Wars and myth; it was marked by the companion book Star Wars: The Magic of Myth. You know the drill: Star Wars is the latest line in a long list of myths that tell universal blah blah blah blah. The latest exhibition touring the world, currently at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, is Star Wars: Where Science Meets Imagination. This time the focus is on the links between Star Wars and real-world science. But again, it’s just a pretense. The exhibition, if we’re honest, is really just about exhibiting really cool models.

Jaime J. Weinman has touched on a topic that fascinates me: trying to pick the movies that will be classics of the future. He has two posts on the topic: one looking at wannabe classics that turn out not to be (here), and one about the process of trying to pick what will hold up later on (here).

This is a topic that interests me a lot; too much, in fact to do it justice right now. But I thought I’d post a couple of quick thoughts in reaction to Weinman’s pieces, since otherwise who knows when I’d get around to it. (For long-time readers, I warn right now that I am going to be repeating all sorts of things I’ve said before that are scattered through the site.)

Weinman has noted the obvious category of movies that don’t age well: Oscar-baiting issues pieces, or middlebrow art films. This is a longstanding observation and complaint and I couldn’t put it better than Pauline Kael who in her landmark 1969 essay “Trash, Art and the Movies” complained about critics praising “ghastly ‘tour-de-force’ performances, movies based on ‘distinguished’ stage successes or prize-winning novels, or movies that are ‘worthwhile,’ that make a ‘contribution’ – ‘serious’ messagy movies.”

Setting the Scene (ACMI, 4 December 2008 – 19 April 2009)

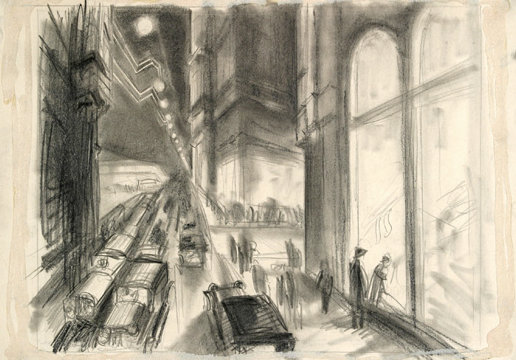

I went along to the Setting the Scene: Film Design from Metropolis to Australia exhibition at ACMI with high hopes and keen interest. The exhibition covers production design in cinema, including the use of sets, locations, and virtual environments. It’s a fantastic and under-explored topic, and one in which I have a lot of interest. As an urban planner, the use of locations and the depiction of our spatial environment interests me a lot (I’ve touched on it in pieces for this site such as this), and the postgraduate research I’m currently doing is focused on these sorts of ideas.

The good aspects of the exhibition flow directly from the inherent strength of the subject matter, and some interesting exhibits. There are things here that film buffs will get a real kick out seeing, such as original design drawings for the modernist house from Tati’s Mon Oncle (as well as a large model of the house); recreated sets from Australia; and – although these have basically nothing to do with the topic of the exhibition – models of vehicles and machines from Speed Racer and the Matrix sequels. The exhibition’s origins as an exhibit by the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin is in evidence in the strong focus on European examples: that’s fine, although the fusion between those parts of the exhibition and the material added by ACMI occasionally feels a little awkward. If all you are interested in is seeing some interesting behind-the-scenes material, some good production stills, and a brief gloss over the topic, you might find the exhibition worthwhile.

I saw Bolt the other day. I won’t get a chance to review it properly, but I will note for the record that it’s enjoyable without being especially memorable. It’s a testament to the professionalism of the creative people at Pixar / Disney: having torn the film down and rebuilt it halfway through production, they still made it slick and fun and involving. Nevertheless, there’s an unmistakable by-the-numbers feel about it: there’s not much sense that anyone had any real passion for this story. Toy Story, you sensed, reflected real interests of John Lasseter; The Incredibles unmistakably meant something to Brad Bird; and Finding Nemo‘s story doubtless had personal meaning to Andrew Stanton. But with Bolt the original director was gone, and it really feels like they only made the film because they didn’t want to write off all the story development. So it’s fun, but passionless.

The most interesting thing about it is actually the 3-D. I have seen a few reviews, like Jim Schembri’s and Stuart Wilson’s, really complement the process. I’m afraid, however, that I don’t buy it. It’s true that it’s way better than old 1950s red-blue 3-D, but that’s faint praise. Beyond the novelty value, does it actually improve the movie experience?

Australia (Baz Luhrmann, 2008)

I’m late to the party on Australia, so this is going to be a belated defence of it. While it’s true that it has generally been positively reviewed (at least in its home country), when a film is as hyped as this one is, faint praise damns. Mix in a few very prominent or particularly negative reviews (such as Luke Buckmaster’s over at InFilm Australia, here), the less-than-expected box-office, and the complete dissipation of any Oscar buzz, and I think it’s fair to say that a sense of disappointment has built around Australia. This was part of the reason that I was so late in seeing the film. I had been pumped for it after seeing the trailers, but it had slipped down in my priorities as it became clearer that Luhrmann hadn’t pulled a rabbit out of his hat and produced a masterpiece. When I finally did see it, though, I was pleasantly surprised. Taken on its own terms, Australia is of course no classic, but it is nevertheless highly enjoyable.

What’s fun about it is how ambitious it is: Luhrmann has mixed up elements of the Australian western (The Man From Snow River), effects-laden war film (Pearl Harbour), epic love story / melodrama (Gone With the Wind), leftist social drama (Rabbit Proof Fence), and more old-fashioned attempts to negotiate Australia’s relationship with its indigenous inhabitants (Jedda), and filtered these disparate influences though the heightened style familiar from Luhrmann’s previous work. Try something like that without it being a little bit of a muddle and you’ve made a bona fide classic. As it is, you do feel the gears change, occasionally gratingly, but what’s surprising is how often it does come together. The film is involving, wonderfully shot, and always entertaining.