One of the best people writing about film is David Bordwell, co-author of the textbook Film Art, a staple of university film courses. It’s great to be able to read his writing for free, on a regular basis, and I’ve plugged one of his articles here before.

Slightly belatedly, I thought it was also worth pointing out his article on shaky camera / fast cut filmmaking, which focuses on Paul Greengrass’s The Bourne Ultimatum. The Bourne flick is long gone from cinemas, but the discussion of this style of direction should be with us for years: how many reviews of modern action films have you seen that complain about this way of shooting? (Certainly all mine do).

What’s notable about Bordwell’s article is that he pushes the discussion well beyond the usual grizzling about this style of shooting and analyses in detail what is going on. As he points out, it’s more than just the length of shots and the shakiness of the camera at work: it’s also about how shots are framed, the proximity of the camera to its subject, the way the camera focusses (and pulls focus), and the placement of cuts (as opposed to simply the length of the shots between the cuts). All this is done in some detail with very clear frame captures from the Bourne film as examples.

Bordwell also expands upon the usual discussion of this style in his discussion of why these things are done. Usually critics lapse into grumpy complaints about ever-shortening post-MTV attention spans at this point, but Bordwell talks about the narrative purposes such a style serves; it raises energy levels, yes, but it also helps conceal mistakes and downplay the over-the-top-ness of some of the action.

I think Bordwell’s spot on, but would point out one other thing that is sort of implicit in his article, but isn’t spelt out: it’s also cheaper to mount an action sequence this way. Pushing the camera back for distant and long-held master shots is expensive. In a car chase sequence, for example, if you pull the camera back for a master shot that shows all the cars speeding down the road, you have a massive logistical exercise in closing off huge sections of road, communicating with all your stunt-drivers, co-ordinating foreground and background action, and so on. All other things being equal, it is likely to become drastically more expensive both the further out the shot is from the action (because there’s a greater area in view that needs to be cordoned off and under the control of the production) and the longer the shot (because the shot is open to more scrutiny, and because moving vehicles will cover a greater area).

This is best illustrated with a couple of examples, which I’ll take from two of my favorite 1980s action sequences: the final chase in George Miller’s Mad Max 2 (aka The Road Warrior) and Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. Despite Miller, in particular, having a reputation as a highly kinetic filmmaker, both have very similar approaches that emphasise long master shots. This is one of the opening shots from the Mad Max 2 chase:

That frame is near the start of the shot: the camera actually flies over the whole convoy of vehicles. Just to underline the point, here’s a really extreme example, with another dramatic re-establishing shot mid-sequence:

Spielberg doesn’t use a helicopter for his establishing shot, but adds the complication of foreground action in this pan that sets up his big action sequence:

All three shots are very effective in laying out the challenge before the hero (the hordes chasing Max, and the number of Nazis Indiana Jones will have to overwhelm). But they would have taken a long time to set up, and shots of that sort of complexity would have been all but impossible in a built-up city environment, where they would require the filmmakers to commandeer whole sections of city for extended periods. (Computer effects change the equation somewhat, by allowing these wide master shots to be done in a computer, but the fundamental point is the same. They just then become very expensive CG shots rather than very expensive “real” shots. Really ambitious computerised master shots also struggle to hold up to audience scrutiny: think of some of the cartoony CG in the freeway sequence of Live Free and Die Hard / Die Hard 4.0).

So while I don’t suggest this is a primary reason that Greengrass shoots the Bourne movies this way, it would be a factor: it is simply much more feasible to set an action sequence in urban locations if you shoot it close and choppy. This was always the case, of course, so I don’t suggest that’s the only or even the main reason people employ this style. But it’s another to add to those Bordwell cites.

As is probably obvious, I’ve got a fondness for directors that shoot in this manner: I think action sequences are vastly more exciting when the audience is clearly oriented, and there’s a real beauty to the way directors like Miller and Spielberg cut their sequences together. (I’ve made this point about Spielberg before, here).

Fortunately, it would be wrong to suggest that this style is dying out. Spielberg recently affirmed his commitment to this way of shooting for Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of Crystal Skull, with Ain’t It Cool reporting as follows from a set visit:

On the style: It hasn’t been shot and it won’t be edited like a modern action film. “I’m not going to change my style.” [Spielberg] said he likes to give audiences a master shot and let them become the editors and decide which of the 8 characters on the screen they’re going to look at. He jabbed at MTV type editing and said this will feel completely within the established INDIANA JONES world.

But it’s not just the old guard like Spielberg who fight the good fight against the shaky-cam brigade; there are still other directors around who shoot and edit for clarity. If you look at the freeway chase in Matrix Reloaded, you’ll see that the Wachowski brothers favour a lot of wide master-shots that clearly orient the different parties in their chase in a manner very similar to the style of Miller and Spielberg. The shots below aren’t the same kind of sequence-establishing shots that I’ve picked out above, but they still show the preference for pulling the camera back (sometimes to extreme locations, such as directly above the action) and clearly arranging the protagonists within the frame:

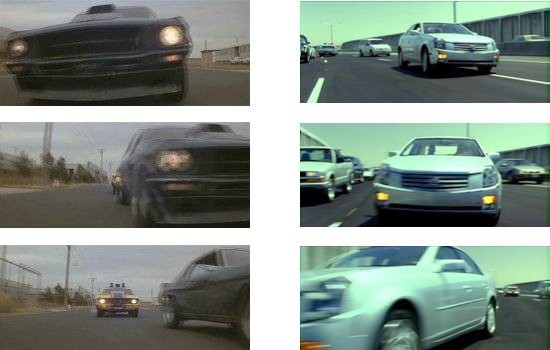

The Wachowskis even employ a shot I always associate with Miller, to the point I have previously nicknamed it the “Miller pan:” a low reverse-tracking shot in which a car sweeps across the frame to reveal the pursuing car behind. This one’s better illustrated with an image: Miller’s original Mad Max is at left, and the Wachowski’s Matrix Reloaded is at right:

The Wachowski sequence is interesting for a couple of reasons. Firstly, the Wachowski brothers were able to shoot this way because they built, at incredible expense, their own freeway to shoot on. By getting off real urban roads they bought themselves the freedom to shoot the sequence in this way (which Miller and Spielberg got from filming in remote desert locations). This reinforces some of what I have said about the cost of shooting such a sequence: it takes a mega-budget Matrix sequel to afford it.

The other point is that the Wachowski’s liking for these wide mastershots dovetails with their fondness for what might be called key shots: really striking, carefully composed shots in which the action is often (though not always) dramatically slowed to “hold” the shot for a few moments. This shifting from the ceaseless flow of images to the picking out of particular key compositions doubtless reflects the Wachowski’s interest in comic books, which are basically a procession of such frames. These shots serve all sorts of other artistic purposes, but in this context it is of note that these key shots are almost always master shots that allow us to reposition all the players in space.

That the comic book influence actually helps restore some clarity and order to the way films are shot is faintly ironic; the comic-book influence on cinema is probably even more derided than that of MTV editing. And perhaps both are blights on the art; but in this case at least, the two scourges are actually working against each other.