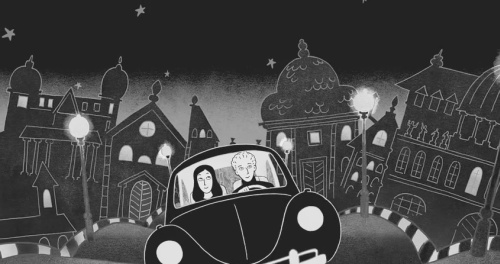

Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud, 2007)

Even those who love animation are prone to dark speculation about its shortcomings as a medium. The lack of live actors and the associated hindrance to truly subtle performances, in particular, is often cited as limiting the potential for serious dramatic work in animated films. The fear is that the relative paucity of full length, adult-oriented dramatic features might not only be due to a lack of courage and imagination on the part of directors and studio executives, but might also reflect actual limitations of animation itself. Thank goodness, then, for Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.

The film is an adaptation of Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novel of the same name, and tells the story of her childhood, adolescence and early adulthood in Iran and Europe, set against the background of Iran’s turbulent politics. It’s difficult material, requiring sensitivity not just to the personal coming-of-age story, but also to the story of Iran through this period. The film is triumphant on both counts. Along the way it demonstrates that the medium of animation not only can overcome its limitations, but actually has some crucial advantages over live action in telling this story.

Probably Satrapi’s greatest achievement is in making the material so accessible: the background and setting will be remote for most western audiences, yet the film is never difficult or aloof. That’s largely because of the focus on universal human experiences – the travails of young Marjane will resonate, at various points, with almost anyone – but in her handling of those more personal elements of the story Satrapi also avoids the film falling into the opposite trap and becoming overly familiar. We have seen a lot of coming-of age stories in the cinema, and the danger with an autobiographical account in particular is that such experiences can seem important to the filmmaker subject, but not to anybody else. Here, though, you really feel for Marjane, who goes from a precocious and dangerously irrepressible child to a shattered, almost broken young adult. It’s quite a journey, and Satrapi manages to take you along it seamlessly, while weaving in plenty of humour and the story of the fluctuating fortunes of a troubled nation.

What are the advantages of animation in telling such a story? There are a few.

It allows a more seamless continuity over time. In live action, it’s hard to follow a character so smoothly through their adolescence, because no actor will convincingly be able to play the part at all ages, and recasting the role brings its own difficulties. A live action film, then, would tend to anchor a life story in one or two main time periods, with perhaps two actors sharing a role, and more of a compare / contrast between childhood and adulthood. Here, we follow Marjane from about 6 or 7 to her mid twenties, and the character ages organically and convincingly throughout. So instead of starkly comparing two stages of life, as live-action would tend to dictate, we get a much more interesting and graduated look at the transition from one to other. It gives a subtle but crucial difference in perspective on the coming-of-age story, and avoids the audience’s link to the character being disrupted by discontinuities of performance.

It can be epic. This is another logistical issue, but again, it’s important. Persepolis spans two continents and the best part of two decades, and places its human story against the backdrop of revolution and war. Placing a personal story against such a background in live-action (even when the conflict is presented in a mostly stylised fashion, as it is here) would require a much higher budget, and the attendant level of risk would bring pressure to compromise on complexity or political pointedness. The unfortunate truth is that while we all love an emotional journey with an epic sweep, such a big scope requires big money, which paradoxically can push filmmakers towards smaller (and hence more marketable) themes. In animation, that contradictory impulse is eased.

It universalises the story. At several points in Persepolis I tried to imagine how the material would play differently in live-action. In the Iranian sections of the film, in particular, I suspect the setting would have become more a foreground element of the film: every scene out on the streets of Iran would have contained countless subtle cues that would have emphasised the foreign-ness of Iranian society to its non-Iranian audiences. This might seem an odd point to make about a film in which a key point is the protagonist’s acceptance of her Iranian heritage, but the film makes its point about Iran and national identity through character, and the characters are established through appeal to universal experience. As I’ve said before, I love the way live-action film can take us to unfamiliar locations and cultures, but here it is not a feeling of unfamiliarity that is important. Just as a comic strip like Peanuts uses the relative simplicity of its visuals to create a generalised version of childhood to which everyone can relate, so Persepolis’ black-and-white graphics keeps the emphasis on the character touches such as the way Marjane absorbs and reacts to things her parents tell her, how she interacts with her friends, and so on. Animation therefore emphasises common experience rather than surface-level differences, which is an advantag when attempting to normalise the exotic.

It allows for a flexibility of tone. The visual style of Persepolis is crisp and stark, and from stills might suggest a sombre drama. Yet the film is constantly funny and full of jokes (including a great shout-out to Rocky III). It’s not that such tone-shifting is impossible in live-action, but certainly I think there’s something about the abstractness of animation that makes it easier to incorporate occasionally absurd humour without it seeming at odds with fundamentally serious material. For example, there’s a scene in the film where a broken-hearted Marjane imagines her ex-boyfriend as a grotesque parody of himself: I don’t think a scene like that could be played in a live-action film without tipping the film into much broader or more fantastic comedy.*

In short, Persepolis is a wonderful film. It has been slowly touring the world in limited release, to much acclaim (it was premiered in 2007, and contested the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature last year, losing to the good but clearly inferior Ratatouille). Hopefully it will find a large and appreciative audience in its Australian release. More importantly, I hope it can push other filmmakers to further unlock the untapped potential of animation.

* Some might feel this contradicts slightly my comments about the mixed tone of Kung Fu Panda. Suffice to say I think animation can accommodate such a mix of tones, but that Hollywood animated features tend not to do so with the skill that Satrapi shows here.