WALL-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008)

Note: this review includes spoilers and my usual rambling ruminations about animation in general.

“There’s something warm and inviting about most animation in just about any classic Disney animated feature, and computers are just never going to pull it off.”

– Thad Komorowski, reviewing WALL-E

Pixar’s WALL-E is a refreshing change of pace. When almost all the productions of their rivals involved a group of animals teaming up and sharing an adventure (a format that even Pixar’s last film, Ratatouille, shared), Pixar have instead gone for a science fiction parable. The result retains their patented sweetness, but gives it a welcome sense of renewal. Pixar’s recent output had been invigorated by the recruitment of the immensely talented Brad Bird, but there was a feeling that Bird’s contribution to The Incredibles and Ratatouille might have been camouflaging a slide in the studio’s work. Certainly Cars, on which Bird did not work, was relatively dull and conventional. WALL-E, however, was written and directed by one of Pixar’s in-house talents, Andrew Stanton (who directed Finding Nemo and co-directed A Bug’s Life), and it shows that there is still a creative spark at Pixar beyond Brad Bird.

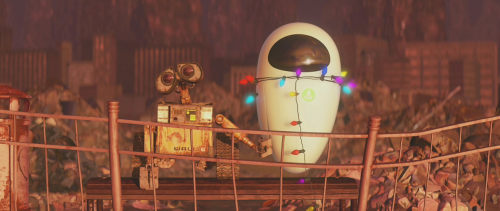

Bird’s films were distinguished by his distinct personality and the feistier approach to the material he tackled: I quibbled with the messages of those two films, but appreciated both the simple fact that Bird had something to say, and that his sensibility was sharper and more caustic than we had come to expect from Pixar. However, in contrast to Bird’s almost elitist approach (discussed in my reviews of The Incredibles and Ratatouille, here and here), WALL-E returns to the warm, humanistic outlook of the earlier Pixar films. Here, though, that approach is transformed by being cross-bred with science fiction of the 1960s and 1970s. The conceit recalls the eco-parables of those decades, telling the story of Wall-E, a robot working diligently to clean a polluted Earth after humanity has abandoned the planet. The robot is entirely alone (save for a cockroach) until a spaceship delivers another robot, Eve. The two robots form a bond, and when Eve makes a critical discovery Wall-E escapes the planet to be re-united with the last remaining humans.

The science fiction aspects of the film push both plot and tone in directions we do not usually see from Hollywood animation. In its first half, particularly, the film has a melancholy atmosphere and muted colour palette that is a long way from the ultra-colourful norm in Hollywood’s animated films. It is here that the film most recalls the feel of 60s and 70s science fiction, with its recurring themes of an abandoned or destroyed planet, and of humanity fleeing to space: the film blends elements from films such as The Omega Man, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Planet of the Apes, Silent Running, and others. What makes this such an interesting hybrid is that those films were generally cold and misanthropic. The human race was either extinct, emotionally desensitised, or responsible for the death of the planet. (Think of Charlton Heston’s final tirade in Planet of the Apes, condemning the humans – in this case responsible for the death of themselves and much of the planet – as “maniacs” and damning them to hell.) WALL-E echoes those themes, portraying an exaggerated version of our own society that has become even more lazy, consumerist and environmentally destructive. Oddly, though, this blends well with Pixar’s fondness for humanity. Once we meet the remaining humans, it is clear that they are not ireedeemable. They are just regular people like us, oblivious to the damage they have done, and – crucially – still retaining the capacity to mend their ways. Perhaps that softens the social satire, but I think its emphasis on a positive message (that we can re-engage with life and the environment if we try) is valuable, and avoids the anti-human message some – such as Mark over at hoopla.nu – have seen in the film. However, I also think it works at the satirical level, since it allows us to recognise ourselves in the future-humans; a more extreme, dehumanised depiction would avoid that self-identification. Certainly it manages a nimbler critique than, for example, Kung Fu Panda’s valorisation of the lazy and useless.

The humans, however, aren’t at the centre of the film. Like 2001, the film depicts future in which our artificial creations are becoming more human than us. The central figure, of course, is Wall-E himself, the inquisitive robot who has developed beyond his original programming. Critics have perhaps made too much of the film’s dialogue-free first half, but certainly Stanton shows an impressive confidence in his ability to carry a story using pantomime and expressive sound effects (the latter by Ben Burtt, the noise-nerd who came up with the vocalisations for R2-D2 back in 1977). Wall-E is, as the film’s relatively few negative reviews have pointed out, a somewhat limited character, due to his childlike nature. But that’s thematically apt, and what’s wrong with a childlike character when the context calls for it? As I’ve said before, talking about Steven Spielberg’s E.T., there’s something unhealthy about the disdain some critics feel for childhood as a subject; it becomes hypocrisy when filmmakers such as Tati, Chaplin and Keaton are granted licence to focus on childlike heroes. Wall-E might be simple, but he is a genuinely charming character, endearingly resourceful and determined, and it is in the treatment of his character that Pixar’s traditional strengths are most in evidence. There is a refreshing sincerity to the characterisation of the little robot. In the DVD commentary for another animated science fiction film, Disney’s disappointing Treasure Planet, there’s moment where the filmmakers talk openly about a particular scene being inserted late in the production specifically to make the protagonist more sympathetic (it’s the bit near the start with Jim Hawkins as a small child). You don’t see that kind of makeshift manipulation in WALL-E. It isn’t that they don’t include moments calculated to elicit sympathy – it’s always the case that filmmakers will need to carefully set up the emotional response of their audience – but in Pixar’s films such moments feel natural because the filmmakers seem to really like their characters. So, for example, when Wall-E panics after accidentally running over his cockroach companion, it is obviously a deliberate bit of business calculated to be endearing; but unlike in Treasure Planet, you feel that Stanton is communicating something about a character that he already liked before they came up the bit with the cockroach.

I don’t understand the objection felt by some, such as Michael Barrier (here), for encouraging such an emotional identification with machines such as Wall-E and the other robots in the film. It simply doesn’t make sense to me that there could be a resistance to anthropomorphised robots when it is appropriate in terms of both plot (why shouldn’t future technology allow artificial consciousness?) and theme (the venerable device contrasting the de-humanising of people with humanising of machines). The emotional identification with robots makes much more sense than it does with the mice, rabbits, toys, cars, blobs of plasticine, giant war machines, or brave little toasters that other animated films have asked us to identify with; given this, I don’t see why using a machine as a protagonist is somehow a bridge too far. Part of the answer, I think, is that some of the writers who have been critical of WALL-E or sceptical of its approach – I’m thinking writers specialising in animation such as Barrier, Michael Sporn, Mark Mayerson, and Thad Komorowski – are blending together a thematic discussion with reservations about the film’s animation technique. A giveway, for example, is Michael Barrier’s comment that “[t]he animation of machines is effects animation, and that’s really all we see in the first part of WALL-E,” and furthermore that the film demonstrates that “computer animation is a dead end, a form of puppetry even more limited than stop motion.”

Surely, though, the distinction between character animation and effects animation is one of intent and effect, rather than simply subject matter: in other words, whatever one feels about the quality of animation of the titular characters in Cars, The Iron Giant, and WALL-E, it seems to me clearly wrong to dismiss it as not being character animation simply because the subjects of that animation are machines. The reference to puppetry, however, makes clear what seems to be the real problem identified in the critiques of WALL-E’s animation, which is that the robots’ bodies are stiff and inflexible. Certainly the animation in WALL-E adopts a significant constraint by never distorting the robots (or at least not obviously enough that I ever noticed it): the animators move Wall-E’s body to express his thoughts and feelings, but never change the actual shapes of the component parts. This contrasts with the approach to the characters in Bird’s two Pixar features, which tried to bring the kind of “squash and stretch” manipulation that is a feature of hand-drawn animation into the world of computer animation. I applauded those efforts by Bird and still feel that his films are amongst the best demonstrations of expressive computer animation, but I think it is overstating the case to say that by sticking with the rigidity of his robots Stanton makes it impossible for them to be effectively animated. Stanton has adopted a handicap, and it might even be true that he was unwise to do so, but that doesn’t mean that the animation inevitably fails. In fact, I found the animation quite fluid and laden with personality, and think Stanton and his animators did a remarkable job of getting us to accept Wall-E as a character. Wall-E’s design might not have the advantage of elasticity, but it still allows him to express thoughts and feelings, and he does so throughout the film. Certainly his handicaps as a communicative character are much less than the vehicles in Cars (despite those characters being granted some flexibility in their models) and the actual animation here is much better than for the elastic but corpse-like penguins in Happy Feet.

To take a broader argument for a moment, even if we accepted the low opinion some feel for the film’s animation, I think it’s unwise to start writing off the medium of computer animation because of technical aspects of how it is produced, as some of the negative reviews of WALL-E have done. Any medium will have things it does well and things it does badly (or, perhaps more accurately, things it does with ease and things it does with difficulty). It is right to be attentive to these things when we discuss films, because they inform our understanding of how and why particular films work and fail. I’ve done this myself in my reviews of both Happy Feet and Kung Fu Panda. However, if we start saying that these issues place fundamental, insurmountable constraints on a whole medium, then I think we stray too far. That is particularly the case when those judgements about the inherent capabilities of a medium are filtered primarily through an understanding of the strengths of another medium (in this case, hand-drawn animation). Film theorist Noël Carroll, in a series of essays in his book Theorizing the Moving Image, has critiqued at some length what he dubs the “medium specificity” thesis: the idea that each artform has inherent properties with implications for what should and should not (or can and cannot) be made in it. Early film theorists such as Rudolf Arnheim and Siegfried Kracauer were very keen on such arguments, but as Carroll argues convincingly, critics and theorists have tended to overestimate the importance of such constraints. Firstly, a medium will have so many competing strengths and weaknesses that defining any particular one as crucial will be impossible; and secondly, the history of development of a medium tends to see artists spilling out beyond the supposed constraints and successfully using the medium for what it isn’t supposed to be good at. I am sure this will ultimately prove true of computer animation. Sure, it might be hard for an animator, manipulating a computer model of a character, to inject the same kind of personality that a traditional animator does when they draw a character. Yet I think it is repeating the critical mistakes of the past if we assume that difficulty means animators cannot achieve character animation that is as good as we see in hand-drawn cartoons.

The evidence is right there in WALL-E. Obviously the film has left some cold, but many others have embraced it. When Wall-E appeared “dead” or brainwashed towards the end of the film, I found it emotionally effective; any difference in my response to, say, the end of Snow White, is one of degree, rather than coming from an intrinsic inability of the medium to create “warmth” or “personality” or – in Barrier’s phrase – “a vital connection between artist and character.” If the dedicated and attentive animators at Pixar can achieve this despite the self-imposed limitations to the elasticity of their characters, doesn’t that demonstrate that there is ample potential for computer animation to achieve such things? Given WALL-E’s interesting generic hybrid between kid’s cute robot movie and adult’s 70s dystopic sci-fi, and its disavowal of so many of the more jarring traits of Hollywood computer animation (star and comedian driven voice-casts; erasure of the personal voice through “filmmaking by committee”; fart gags; unmotivated pop-culture references; excessive self-referentiality), I find it hard to see it as anything other than a very enjoyable step forward.