A while back I posted about Courthouse Square, the classic town square used in countless film and television productions. As I argued then, I think these backlot places are interesting because they at once reflect and shape our ideas about community. When Hollywood production designers build a backlot set, they will aim for something that is at once familiar yet generic (since it will be used in many productions), while simultaneously desirable (since Hollywood films tend to show a world that is a little bit more exciting and interesting than our own). That’s the part where they reflect our desires.

Yet once built, those sets reappear in many productions. Over time, with repetition, those generic backlot communities can come to actually shape our image of community. I don’t want to over-sell this idea: obviously we don’t simply passively absorb a picture of the world from movies and then start to believe this is the way the world is, or should be. But I do believe that pop-culture iconography is party of the language we draw on to make sense of the world, and that Hollywood’s images of the quaint small towns, leafy suburbs, or the polluted big city become powerful visual signifiers that influence the way we picture different types of community.

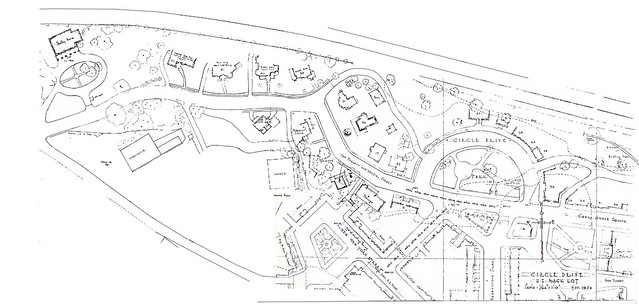

The Courthouse Square set is a good example of that, but the attached residential street might be an even better case study. Known as Colonial Street, and constructed in 1950, it was connected to the western edge of Courthouse Square via a semi-circular park area known as Circle Drive. The configuration can be seen in this plan of the Universal backlot from 1950: Colonial Street occupies the top left corner of the plan. (All the images in this post can be enlarged – just click on them).

Here’s the eastern end of the street, showing its connection with Circle Drive, in Douglas Sirk’s 1953 film All I Desire. In this example it is serving as an archetypal turn of the century small community along the lines that I discuss in my extended essay on the classic Hollywood town.

Sirk’s All that Heaven Allows includes an almost identical establishing shot, below, using the street as a contemporary (ie 1955) small town street. In that film Colonial Street can be thought of as quasi-suburban: while the film is nominally set in a small town, its focus on the alienation of the house-bound middle class woman is very much of a piece with the anti-suburban works appearing around this time, like The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (novel in 1955; filmed in 1956).

Here’s a shot from within the street, again as an early twentieth century small town, in Stanley Kramer’s Inherit the Wind.

One of the most frequently seen buildings on the street was a distinctive multi-gabled house constructed at the bend in the centre of the street. It’s where Jane Wyman lived in All that Heaven Allows.

Here it is in the 1955 thriller The Desperate Hours.

But perhaps most famously, it was the house of the Cleaver family from season 3 onwards of Leave it to Beaver.

This example better illustrates what I mean about the shaping of an idea about community. Leave it to Beaver is perhaps the definitive positive depiction of suburbia from the early post-War era, when the middle class flight to the suburbs was at its height. It is one of those cultural products that epitomises all that people wanted from the suburbs, which are depicted as an attractive and harmonious setting in which to raise families. Colonial Street is particularly prominent, with the show frequently showing the kids roaming their neighbourhood unsupervised, emphasising the safety and wholesomeness of the suburban environment. For a generation of Baby Boomers, Leave it to Beaver‘s Colonial Street was arguably the iconic suburban street.

The street still exists – sort of. In 1981 it was moved across the Universal lot, and the houses reassembled in different configurations. Its 1980s incarnation can be seen in the Joe Dante film The ‘Burbs, where the street was named Mayfield Place as a nod to the fictitious community in which Leave it to Beaver was set.

Perhaps most famously, though, the street has become Wisteria Lane in Desperate Housewives.

Here the street’s iconicness is subverted: its physical embodiment of such a picture-perfect suburbia is meant to serve as an ironic setting for the soap-opera shenanigans that play out on the street. Interestingly, the other remaining backlot street of similar vintage has similarly been utilised for ironic effect: the suburban street from the former Columbia (now Warner Bros.) ranch was used as the too-good-to-be-true 1950s sitcom suburb in Pleasantville.

It’s interesting to think about what it says about post-war urban planning that it is so much more difficult to accept this kind of positive portrayal of suburbia as anything other than irony or nostalgia.

For more about the street, I recommend Kipp Teague’s invaluable site.