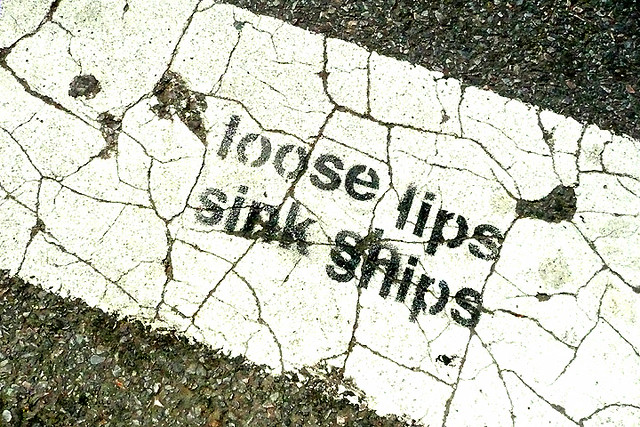

Sir Humphrey: How are things at the Campaign for the Freedom of Information, by the way?

Sir Arnold: Sorry, I can’t talk about that.– Yes Minister, “Party Games”

Victorian planners will have seen the announcements about new zones this week. This is a big planning story and one I hope to write more about once the detail is available. But it also marked the conclusion of my own curious adventure through Victoria’s Freedom of Information procedures.

Through 2011 I had been thinking a bit about residential zones, and contemplating writing something for Planning News about how zones could better facilitate the rolling out of local housing solutions. My thinking had been that the focus on fast, medium and slow-growth zones, evident in the earlier discussion papers, was misplaced. For me the focus needed to be not so much about setting different “temperatures” of redevelopment, with all the political challenges that can involve, but instead being more specific about the forms preferred development should take.

As I thought about how such controls could work, I became increasingly frustrated that the Advisory Committee report on residential zones, finished in 2009, was not publicly available. This was, after all, the biggest single piece of work on the subject, and DPCD and the Minister had sitting on it for more than two years. I asked DPCD for it, but got the expected answer: they weren’t releasing it until the government’s response was ready.

This is an attitude to the release of information that has been getting more prevalent and which drives me crazy. It wouldn’t hurt anybody for such a report to be in the public realm while a response is being considered, as has occurred for numerous reviews in the past. So I lodged a Freedom of Information request seeking the Advisory Committee’s report.

I had two purposes in doing so. Firstly, I was legitimately interested in getting the report and seeing what it said. I felt access to it could spur policy discussion that had been effectively on hold for more than two years while the profession waited for its release. Secondly, though, I thought it was worth challenging the approach to information management that the Department has taken in this and other similar situations. The withholding of information for reasons of political expediency has become the norm, and the general culture of the Department (and government more widely) is excessively secretive. It seemed to me that some push back against this approach had intrinsic merit, regardless of the outcome.

My request was lodged on 14 February 2012, and the Department had sixty days to respond. If they don’t respond in time, they are deemed to have refused the application and that “decision” can be appealed to VCAT (you can find more about the process here). When that time ticked over, I lodged the application with the Tribunal, taking advantage of the fact that such appeals are free (if they had refused the request in time the application would have been $219). Shortly after I lodged that appeal, I got correspondence from DPCD confirming that would have refused my request anyway.

The basis of the refusal was that the documents were exempt under Section 30(1) of the Freedom of Information Act, which protects internal working documents. Internal working documents aren’t automatically exempt, however: that section is also subject to a test as to whether release is contrary to the public interest. That test therefore became the key issue that VCAT would have to decide.

We had a directions hearing before VCAT on 1 June 2012, at which it was agreed that by 22 June 2012 I would lodge a statement detailing the legal and public interest grounds on which I relied. DPCD would then respond with their own statements by 13 July, with the matter then set down for a hearing on 17 July. So I went away and wrote my submission.

What follows is that submission, which I circulated to VCAT and the Department on 19 June. I’ll return at the bottom with the details of how it then panned out.

• • •

Background

I have made an application under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 for a copy of the report of the Advisory Committee into new Residential Zones.

The Advisory Committee report is a key output of the review of the residential zones, a policy review underway since 2007. The timeline of the review of the residential zones is as follows.

June 2007: Making Local Policy Stronger review recommends review of residential zones.

October 2007: Government releases “five point priority action plan” committing to recommended review of residential zones, scheduled for completion by the end of 2008.

February 2008: Discussion paper on the new zones released.

February 2009: Draft zones released for consultation.

April 2009: Consultation concludes with 430 submissions having been received.

c. April 2009: Advisory Committee appointed to prepare a report with recommendations on the content and implementation of the new zones by August 2009.

August 2009: The Advisory Committee submitted its report to the Minister.

No further output of the review has been publicly released.

I made my formal Freedom of Information request for a copy of the Advisory Committee report on 14 February 2012 after a request directly to the Department was declined.

Legal Contentions Relied Upon

It is my understanding that the legal grounds in this case are essentially undisputed.

The Department have indicated that they oppose release on the grounds that this is an exempt document under Section 30(1) of the Freedom of Information Act. That Section is as follows:

30(1) Subject to this section, a document is an exempt document if it is a document the disclosure of which under this Act—

(a) would disclose matter in the nature of opinion, advice or recommendation prepared by an officer or Minister, or consultation or deliberation that has taken place between officers, Ministers, or an officer and a Minister, in the course of, or for the purpose of, the deliberative processes involved in the functions of an agency or Minister or of the government; and

(b) would be contrary to the public interest.

There is no dispute that section 30(1)(a) applies to the document. However, obviously for the exemption to apply, 30(1)(b) must be met as well.

However, the Department argued that release is contrary to the public interest. In correspondence of 27 April 2012 from the Department’s Manager – Freedom of Information, they explained this position as follows:

…I note that the requested material comprises advice provided to the Minister for his consideration.

The Minister has yet to reach a final decision on the report, and its release at this stage may provide a misleading view of policy in an area of sensitive public and commercial concern. Disclosure of the report prior to the Minister’s decision contains the potential to misrepresent the Minister’s views and future courses of action on these matters. As a result, I find that it would be contrary to the public interest to release the report, and it is exempt.

The Statement pursuant to Section 49 of the Victorian Civil and Administrative Act 1998 provided by the Department on 16 May 2012 did not expand on these grounds.

I argue that release is not contrary to the public interest, and that therefore the document is not exempt. Indeed, I would argue the contrary case: not only is it not contrary to the public interest, but that release of the document is strongly in the public interest.

The remainder of this submission therefore focuses on this question of the public interest in this matter.

Public Interest Grounds Relied Upon

I will address the public interest grounds in two parts. Firstly, I will argue the case that release is not contrary to the public interest. Secondly, I will examine the public interest grounds that favour release.

Why Release Would not be Contrary to the Public Interest

Release will not stifle the provision of free and frank advice

While not explicitly relied upon in the Department’s statement, it is worth considering perhaps the classic reason that not releasing internal advice may not be in the public interest, since this goes to the core of the intent of Section 30(1) and raises important issues about the nature of the particular document requested in this instance.

Section 30(1) serves an important role in protecting the deliberative functions of government and allowing public servants to give full and frank advice. This is a crucial function, and in my view seems likely to have been the key reason for the inclusion of the exemption when the Act was drafted. In considering the current case, then, it is worth noting that this key rationale has no application to the current matter given the nature of the document.

Advisory Committees are appointed pursuant to Section 151 of the Planning & Environment Act 1987. While that section is quite open-ended, the practices surrounding the operation of Advisory Committees are well established. They are managed by Planning Panels Victoria (PPV). While notionally part of the Department, in practice PPV operates largely independently. Advisory Committees are drawn from a pool of panel members, including a few full time panel members and about eighty sessional members who do not (for the most part) work for the Department. While the Department frequently provides some technical and administrative assistance to PPV, PPV also have their own dedicated administrative and research staff.

The nature of an Advisory Committee report, then, is that it is a largely independent opinion, quite distinguishable from an internal product of the Department. While there is no dispute that the report counts as internal advice for the purpose of Section 30(1)(a), in considering the public interest of release, it should be taken into account that the nature of the report makes it far closer to an external input than most documents that would be protected under the Section. The public interest questions would quite different if, for example, I had sought access to the Department’s advice to the Minister about whether he should accept the Committee’s recommendations.

Crucially, Advisory Committee reports are prepared with an expectation of public release. While there is to my knowledge no legislative obligation to do so, these reports are invariably released at some point in the process, whether it is before or after a decision has been made.

The Advisory Committee would therefore write in the expectation that:

- They have been appointed specifically because an independent perspective outside of the Department’s is sought; and

- Their report will be publicly released at some point.

I submit that in light of there is simply no prospect that exposure of Advisory Committee reports in this or any other instance would cause future Advisory Committees to approach their work differently. They already write with an expectation that they may contradict “official” positions, and that their work and recommendations will be subject to public scrutiny.

The classic basis for the application of Section 30(1) therefore does not apply.

Release would not cause a “misleading view of policy” or public confusion

It should be acknowledged that the Department does not seek to rely on the grounds discussed above. As noted, the Department’s reasons cite only the “potential to misrepresent the Minister’s views and future courses of action in these matters.”

This reasoning seems closely related to the formulation from the Commonwealth case of Howard v The Treasurer of the Commonwealth (1985) 3 ALR 169, referred to in Wells v Department of Premier and Cabinet [2001] VCAT 1800, which suggested that:

Disclosure, which will lead to confusion and unnecessary debate resulting from disclosure of possibilities considered, tends not to be in the public interest.

It is considered that current case highlights the dangers of applying such a formulation too widely. It is also submitted that the risk of release leading to “a misleading view of policy,” “[misrepresentation] of the Minister’s views,” or “confusion and unnecessary debate” is significantly exaggerated.

At its simplest level, these concerns have no basis given the nature of the document. The document does not purport to be a statement of the Minister’s views. For anyone to assume that it represented the Minister’s views would be simply mistaken. Were it to be released, it would be abundantly clear that it was an input to a process, not an expression of the Minister’s views or a statement of policy.

It is considered that the nature of the document, discussed in the previous section of this submission, is sufficient to establish this level of “distance” between it and a statement of official or likely policy. However, in this instance there is considered an especially strong basis for assuming that such confusion is unlikely. This document was commissioned by a previous government, and delivered over two years ago, well before the November 2010 state election. The duration of time involved, and the fact that the government has changed in the interim, would further increase the “plausible deniability” for the government with regards to its findings.

It should be noted that while in some cases Advisory Committee reports are held until the government has its full policy response ready, they are also often released ahead of a full government response. For example:

Review of Heritage Provisions in Planning Schemes: Prepared in August 2007. Released, but no implementation has occurred.

Advisory Committee Reviewing Advertising Signs Provisions in Planning Schemes: Prepared December 2007. Released, but only limited implementation occurred. Response to the most significant recommendations remains pending.

Victorian Planning System Ministerial Advisory Committee: Released in May 2012. Only a sketchy response document was released by the Government at the time of release.

In such cases, it has been clear that the government is still formulating a response, and it has been widely understood that the Advisory Committee’s views are not those of the government. The last of these Committees, in particular, involved issues of equal public concern as those touched upon in the residential zones review, and raised many issues and recommendations to which the Government has either not responded or has offered only a cursory response. There has not been any widespread misunderstanding that these reports represented the Minister’s position.

It should also be noted that in the current instance many of the options under consideration by the Advisory Committee are already in the public domain. A discussion paper and draft controls have already been released. These have already raised a range of possible policy solutions that may or may not be taken further by the government. This means that much of the potential confusion or debate about possible policy is already occurring. While I can only speculate without access to the document, I would respectfully request that in its deliberations the Tribunal consider the extent to which the potential policy options evaluated by the Advisory Committee actually fall far outside the options already in the public realm as a result of the earlier released work. If the Advisory Committee’s discussion is broadly centred around the same options, I would argue that the potential to mislead the public about policy formulation is limited.

A final point should be made about the assertion that disclosure leading to “confusion and unnecessary debate” tends not to be in the public interest. I would argue that such an approach risks running counter to the intent of the Freedom of Information Act by taking an overly protective attitude to the ability of the public to assess and process information. I submit that the public is not as readily addled or alarmed by public policy debate as such an approach would suggest, and does not need to be protected from exposure to the mechanics of policy formulation.

In making this point it is helpful to draw a distinction between the current situation and the kind of instances where the approach to “confusion and unnecessary debate” might be in the public interest. It is recognised that sometimes disclosure of options can distort public debates, or be overly alarming for the community.

As an example we might consider a hypothetical situation where internal government advice mentioned a highly controversial solution to an issue: so, for example, if an internal options paper on dealing with expanding populations mentioned, in passing, the possible response of limiting couples to one child. In such a case the government might unjustifiably have to expend political capital responding to a policy option that was never plausibly under consideration. More importantly, the public’s understanding has been hindered by the discussion of an implausible policy option. Similarly, members of the public might be unnecessarily alarmed about the impact upon them. The public interest in forestalling such outcomes is genuine.

By contrast, the Advisory Committee report can be presumed not to include speculative policy options that are likely to distort public understanding of what the government is considering. The document comes late in a review process that has already included a discussion paper and draft zones. The level of public speculation would be simply consistent with healthy public policy discussion about plausible policy options, and would not be expected to be of a nature that would be contrary to the public interest.

Revisions to the possible formulations of residential zones are also simply not contentious enough to have the potential for either mischievous misrepresentation, or genuine misapprehension, that would require their suppression. This is particularly the case when many of those options are already in the public realm, as noted. It is also more likely to be the case when the options under discussion are high level options. For example, the discussion of a residential zone allowing for intensive development would be far less alarming or potentially misleading than speculation about applying such a zone to a particular site.

Indeed, I submit that the approach to Section 30(1)(b) taken in this instance risks being so broad that it undermines the intent of the FOI Act. If disclosure is deemed to be contrary to the public interest in any case where it might provide a “misleading view of policy,” it would be difficult to see how any internal document that did not accord with a finalised policy position would ever qualify for release. Such an outcome would be contrary to principles of good governance and the functioning of the FOI Act.

The concern about “misleading view of public policy” taken by the Department in this situation is dangerously close to considering Section 30(1) as serving the government’s communications needs. In other words, it seems the document may be held from release largely because the government wishes to have a unified message about its intentions, and (more recently) to avoid criticism for an extended failure to act on the Committee’s recommendations. That may indeed be in the government’s interest. However I submit that it is not in the broader public interest to require the timing of a document’s release to be more convenient for the government’s communications strategy.

I would respectfully submit that in order to preserve the integrity of the FOI process and open policy debate, the Tribunal should reject the approach to the public interest test taken in this instance. The public do not need to be protected from the knowledge that a range of policy options are being considered by the government.

The Public Interest Case for Release

The issue of public interest is a matter of balance. The potential arguments against release should be weighed against the arguments for release. I have already argued that the case against release is not strong simply on its own merits. However I also believe that there is a strong positive case for release. From its supplied decision, there is no evidence that the Department weighed these potential benefits in forming a view on the public interest consideration.

My request for the report comes from a desire to further public policy discussion. I was formerly the co-editor of Planning News and have written widely on urban planning in Victoria, with a particular focus on planning system reform. As a practicing planner I work daily with members of the public who are dealing with the difficulties of the current planning system. I therefore take a strong interest in ways in which the planning system can be improved and have written a number of extended articles for Planning News exploring ways in which this could occur. I have also made multiple submissions to government reviews, most recently a submission to the Victorian Planning System Ministerial Advisory Committee that was quoted at some length in the Committee’s report.

I believe that review of the residential zones is a centrepiece of planning system reform and that there is intrinsic benefit in seeing this policy reform more widely discussed. The Advisory Committee report is, it can safely be assumed, a major piece of policy work in this area. Many urban planning professionals and community members took considerable time to make submissions to it. They did so in the good faith assumption that their efforts would further public policy development, and while those submissions have been released on the Department’s website, the Committee’s synthesis and analysis of them has not. That has deprived the profession and wider community of the opportunity to discuss the findings of the report.

Had the report been released when it was ready in late 2010, there would almost certainly have been extensive coverage in journals such as Planning News. The report would have been dissected and discussed. Public reaction would have given the Department and Minister a sense of what policy challenges lay before it, and what aspects of the controls might be embraced. It is possible that mistakes or problems might have been found in any draft controls, allowing them to be averted. Councils could have started to consider where they may wish to apply new zoning solutions. The incoming government could have considered how it wished to make use of the Advisory Committee’s findings, and hit the ground running when it came into power. Other reviews, such as the wide-ranging Victorian Planning System Ministerial Advisory Committee review (the so called “Underwood Review”), could have drawn on its findings.

In short, the Department could have drawn on months of public discussion and scrutiny of the Committee’s findings, allowing its implemented solutions to be more robust when they did appear.

Instead, the absence of this central piece of work has actively worked to suppress policy discussion. The government claims that release of the document is now likely to occur this year, but release has been described as imminent for the duration of the period since its preparation. Urban planners who wish to write articles about residential zones for journals such as Planning News will be understandably reluctant to expend the time when a major piece of work on the subject was about to be released. When the timeframe for a review such as this slips out to multiple years, public policy debate is stifled for a significant period, and the policy work starts to lose currency before it is even released.

In this case, there has not been a public output from this review since February 2009, and no notable status update since the Department’s website acknowledged receipt of the Advisory Committee report in late 2010. Such policy atrophy is not in the public interest, and I suggest that the failure to release the Advisory Committee report only contributes to this kind of stagnation. A detailed piece of work in the public realm would have helped to maintain momentum behind the proposed initiatives.

The approach to Section 30(1) urged by the Department would see the non-completion of the review as sufficient justification for its non-release. If such an approach is taken the situation should not be allowed to persist indefinitely, or non-completion of reviews would become an indirect means of suppressing inconvenient documents. In this case, the current review was announced in October 2007 and due for completion by the end of 2008. It is therefore a fourteen-month-long review that is running forty-two months late.

The government has therefore had ample opportunity to formulate a considered response. There is a strong public interest in ensuring timely policy formulation, and the non-release of the Advisory Committee report only facilitates a lack of action and policy paralysis.

Conclusion

I submit that release of the Advisory Committee report would clearly be in the public interest. Its release will not hamper the provision of frank advice to the government. It is unlikely to cause confusion or misunderstandings about government policy since the document is clearly distinguishable from a statement of such policy.

Instead its release will inform public debate and allow for the Department to make a more informed response to its findings. Requiring such transparency would also have its own intrinsic benefit in encouraging a more open, transparent and timely policy development process in both this review and other reviews to come.

I believe that the approach to the public interest test of Section 30(1) taken by the Department in this case has the potential to construe it so broadly that it would end up suppressing a wide range of documents that are simply inconvenient for the government to explain. This is not an approach to the public interest test that the Tribunal should condone.

For these reasons, I respectfully request that the Tribunal allow my appeal and order the release of the Advisory Committee report.

• • •

So I made the submission and waited with interest for the Department’s statement, due 13 July 2012.

On 4 July I instead got an email from the Department’s Manager – Freedom of Information, saying that the report now would be released to me. However, they couldn’t say when. Nevertheless, they suggested that the hearing be vacated to avoid unnecessary further costs. The suggestion was not to set a new date for the hearing, but rather to adjourn to an Administrative Mention in four weeks.

There was some back and forth at this point, but essentially my argument was that if they were agreeing to release it, they could just release it. If on the other hand they wouldn’t actually send it to me, then as far as I was concerned, they were still refusing release and nothing had changed. I was reluctant to vacate a hearing I’d waited some time for, and for which I’d already circulated my statement, on the basis of a promise that the report would be given to me at some unspecified future date. In any case, they needed to make a request of VCAT to vacate the date if that was what they wanted, so I waited to see what would happen next.

On 11 July, two days before day before the DPCD statement was due to be circulated, the Minister announced the new suite of zones. By the next day there was information on the DPCD website, although this curiously lacked either copies of the new zones or any detailed background information, such as the Advisory Committee report. (The paper they did put up instead is astonishingly flimsy basis to support the biggest overhaul of the Victoria Planning Provisions since their introduction in the late 1990s). The new zones are promised to go up on the site on 17 July, with the unusual delay of a week between the announcement and posting of the supporting information unexplained.

On 13 July, the day DPCD would have had to circulate their statement defending their refusal of my FOI request, they instead acquiesced and sent me the Advisory Committee report. You can read it here. As I write it is not yet on the DPCD website: I assume it will probably go live there on 17 July, simultaneous with the scheduled release of the zones. If so, that release will be the same day we were scheduled to hear the case at VCAT.

The whole thing is deflating. While I’m pleased the document is now in the public realm, it would have been good for the principles involved to have been heard by VCAT to get some view on whether this kind of extended withholding of information can legitimately said to be in the public interest. Such a finding could have had considerable benefit in encouraging more open and rigorous policy formulation in future.

It’s also disappointing to consider the potential for abuse of the FOI process highlighted by this situation. The Department have refused the initial request, and delayed release for a considerable time, but by releasing the material at the last minute have avoided having to defend their position and averted any risk of an adverse finding at VCAT. If they had responded within time to the initial FOI request, it would have cost me more than $200 to lodge the appeal, and so in practice I never would have gotten that far. (The government have announced their intention to appoint an FOI Commissioner, who would have heard the initial review in such a situation, but my understanding is that those arrangements are not yet in place).

All this for a document that wasn’t very sensitive. It doesn’t need to be like this.

Image by J.L. McVay and used under Creative Commons Licence. Click it for details.