On 22 September 2023 all planning schemes in Victoria were changed to make a range of the ResCode Standards (which apply to single houses, and medium density housing up to four storeys) deemed-to-comply. This is a change that has been suggested for a while, and which I have long argued against (I wrote a long post about it here, which goes into the long messy history of this issue).

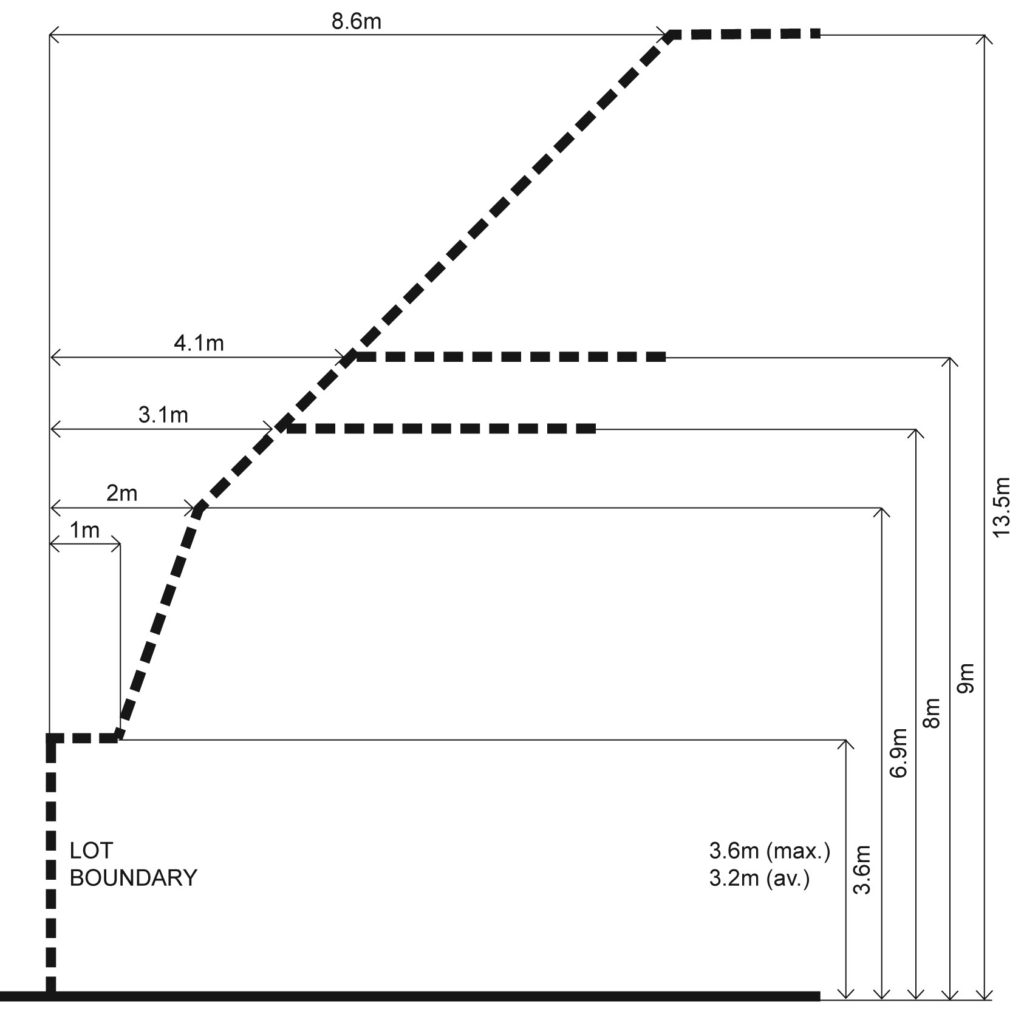

The Standards were supposed to work as benchmarks – effectively, guides to a typically acceptable outcome. However they were always supposed to be applied with a view to achieving a corresponding overarching Objective, which was a more subjectively worded statement. (The side and rear setback Objective, for example, is “to ensure that the height and setback of a building from a boundary respects the existing or preferred neighbourhood character and limits the impact on the amenity of existing dwellings.”) This meant a decision-maker could decide a particular site context warranted a greater setback than the Standard.

The new changes mean that, for the Standards that are set in purely numeric terms, satisfying the benchmark means that the accompanying Objective is deemed met, and a decision-maker can no longer argue that a particular circumstance warrants a different approach. For now, only the 13 Standards that were expressed in purely quantitative terms have been converted to operate this way, but the state government has foreshadowed the rest will follow. (The same previous post explains a version of this model they proposed in 2021, which explains one way this may work).

The effect of this is that if a proposal meets those 13 Standards it would be very hard for a decision-maker to refuse the application. For the moment, there are still those other qualitative Standards, and these notably include an open-ended standard about neighbourhood character. However an amenity argument against such a development would be almost inarguable. Even thinking in neighbourhood character terms, an issue arises because the 13 quantitative standards are deemed to have addressed character issues too. The side setback Objective quoted above, for example, refers to character. If the proposal fits inside the “box” described by these 13 standards, it will be deemed to be an acceptable character response with regards to street setback, height, site coverage, side and rear setbacks, and walls on boundaries. The scope to argue character arguments is pretty limited.

So what does this mean in practice?

Many will read the above and think it sounds like a great idea. We need housing – why should we be arguing about issues where the provisions set a standard? However to properly understand the change, we need to stop talking in the abstract and look at what the ResCode standards actually say.

I don’t have a concern with deemed-to-comply standards in principle. While I think in practice it will be hard to design a fully deemed-to-comply residential code for larger medium density housing proposals, I think it is at least possible – we already do this for a large proportion of single homes, and have done it in the past for two-dwelling (dual occupancy) developments.

What I do have a concern with is using the existing ResCode Standards this way without modification. These provisions were never intended to work this way, and were not framed with an intention that a Standard-compliant development would be generally acceptable. Having assessed what must be many hundreds of ResCode developments in my career, it is very clear to me that the actual outcomes under ResCode are very dependent on the qualitative and contextual elements of the provisions. In my view, advocates for deemed-to-comply ResCode tend to underestimate the “work” that those aspects of the controls do.

There is also the issue that more than a decade has been spent rolling out new residential zones to guide levels of change expected in areas. Much of that work will be wasted if development outcomes are now increasingly aligned, as the ResCode Standards do not change between the default form of each the three main zones.

That’s just my view, though. What I think is indisputable, though, is that we should be starting with an informed perspective on what deemed-to-comply ResCode looks like. If the government, or other advocates of the approach, think this modification of the provisions leads to goof outcomes, we should be able to see that for typical lots. Traditionally under ResCode it was hard to say what a compliant design envelope looked like, because it was supposed to be influenced by the site’s context.

Now, however, we can sketch out an envelope for typical lot sizes. If a building fits within those envelopes it will be deemed acceptable against most aspects of the Code, and as I said will be very hard to refuse. The amendment introducing deemed-to-comply ResCode Standards should have been supported with that kind of analysis and explanation, including drawings of typical compliant envelopes and typologies on common lot sizes. That would have allowed an informed perspective on what otherwise seems like an obscure and technical change. There is, however, no sign that any such analysis has ever been done.

By now you surely know where this is headed – I have downloaded a copy of Sketchup to have a go at doing such drawings myself.

A few notes of explanation about these drawings:

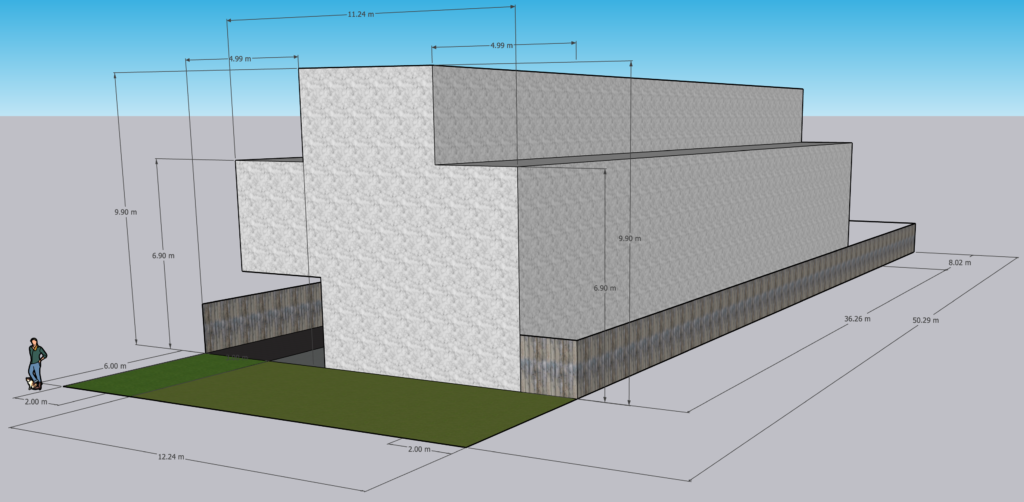

- The site I used is a 766sqm site, with a frontage of 15.24m and depth of 50.29m. Whether this is a typical medium density redevelopment site will depend on where you live or work; for me this is a generous but not enormous “traditional” lot on which you would commonly see some infill housing developed. I got these dimensions from a real planning appeal I worked on in St Albans; I wanted to be able to check my various assumptions against a real example as I went.

- These sketches are intended to show a plausible compliant massing. They are obviously not real designs. They are not, however, the full envelope either. Instead I have tried to show a plausible development form. The basic template is a pattern I describe in my book about the Victorian system (at page 224) – side-facing units with screened balconies arranged down the lot. It’s not a typology I am a fan of, but your mileage may vary, and it is what ResCode has traditionally led to in situations such as the Residential Growth Zone where less weight is given to surrounding context (in other words, where they were already closer to working in a deemed-to-comply way).

- There are Standards that can’t be modelled in this scenario, such as setbacks from adjoining windows. In my experience these do not usually end up greatly modifying these envelopes, except perhaps on an east-west lot where north facing windows may force a greater setback. However it is an inherent limitation of this exercise that is important to acknowledge.

- I have assumed a 6m front setback (unless setbacks are very large, the front setback is typically derived from the average setback of the adjoining lots).

- There are a few hard to account for functional vagaries – like turning circles into garages – so take these as informed approximations of a plausible form.

- These are all based on the “default” ResCode controls, without local variations.

- I have never used Sketchup before so please excuse the slight jankiness of these drawings.

I say a little bit more about assumptions behind the drawings for each zone below. You can click the drawings to enlarge.

In all cases these are just the standard-compliant forms. Developers can still apply for variations to the standards, but they would be more open to challenge by objectors or the decision-maker.

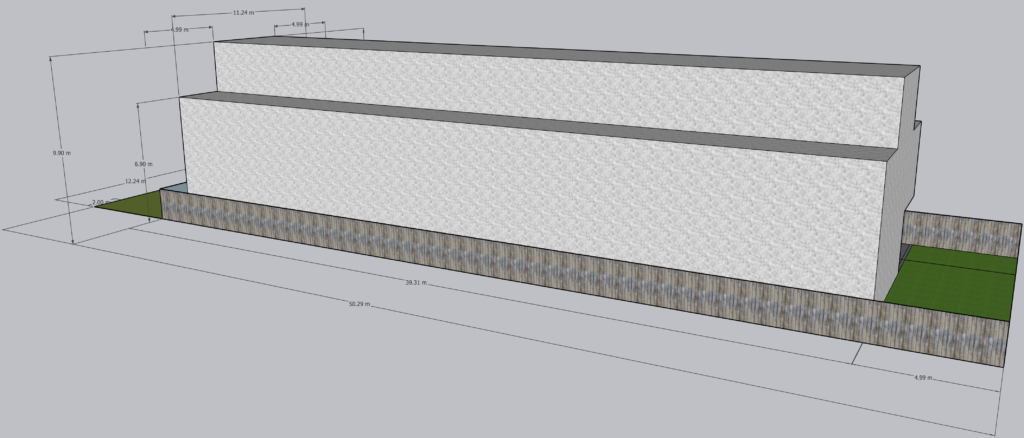

General Residential Zone

In the General Residential Zone, the envelope leads to the three-storey form pictured above. The building can be higher under the zone (theoretically up to 11m) but in practice the side setback requirements will constrain the height on a lot of this width. I have shown a 9.9m three-storey height, which is the height allowed at a 5 storey setback from each boundary. It could be a lower, but that would also allow the third storey to be correspondingly closer to the side.

The building above has a site coverage of about 53%, actually well under the Standard of 60%. However with this configuration the separate Garden Area control kicks in first – 35% of the site must be Garden Ares. (This has a complex definition, but essentially amounts to garden spaces over 1m wide, with driveways excluded.)

I provided a 2m gap along the side without the driveway. The walls could partially extend to the boundary here, but this would require shortening of the overall form to continue meeting the Garden Area control.

Because the building length is being set by the Garden Area control, if the front setback were reduced, an equivalent setback increase would have to be added at the rear to make up of it (essentially sliding the building forward).

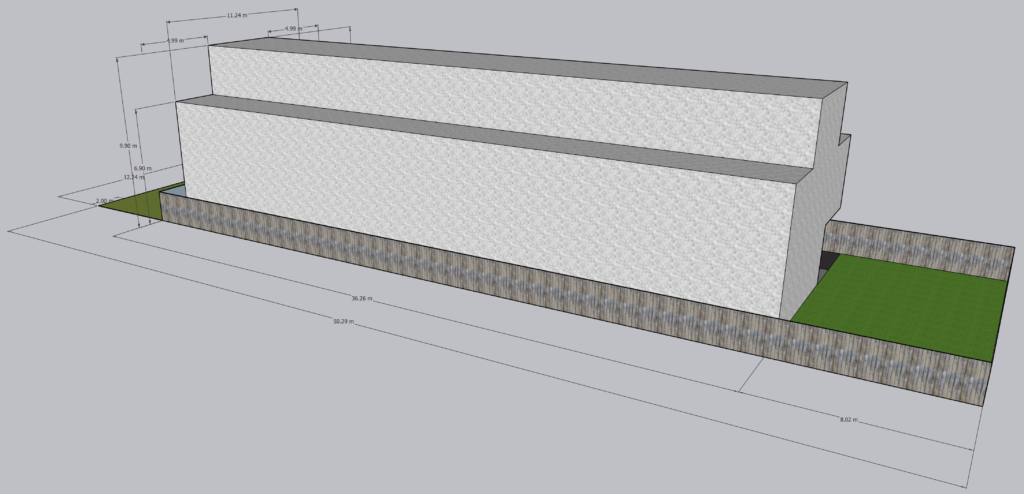

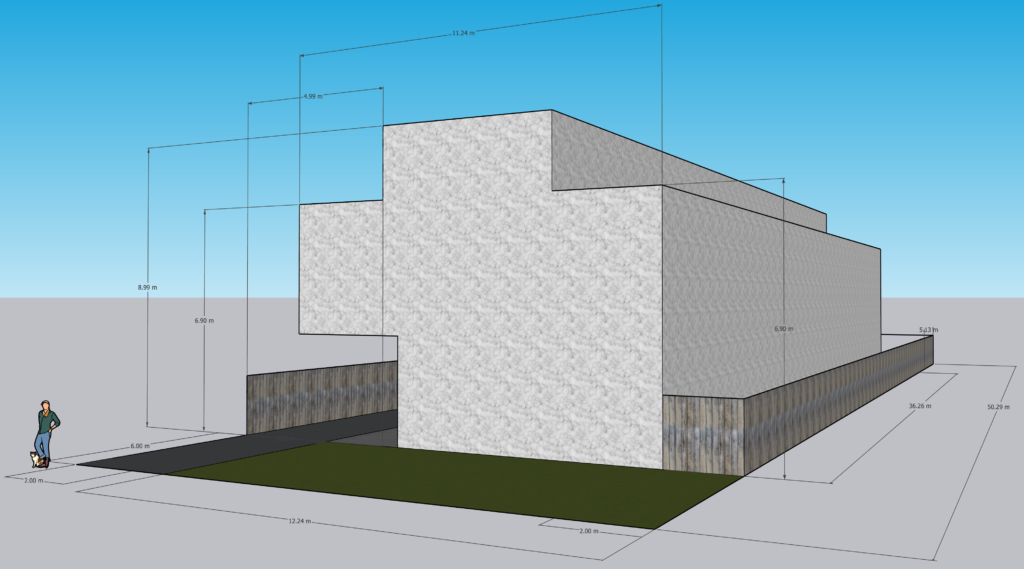

Residential Growth Zone

Under the Residential Growth Zone, the constraint of the Garden Area control is removed (there is none in this zone). The setback from the rear boundary is now constrained by the side setback control. Come to think of it, this means the ground and second storeys could be a little closer to the rear, here – although only a little without varying the standards, as the site coverage is 57%. Similarly, if the required front setback were less than 6m, the building could be a little further forward – but only a little, as it would be constrained by the site coverage standard.

As with the General Residential Zone, overall height could theoretically be higher, but actual height will be constrained by the side setbacks standard.

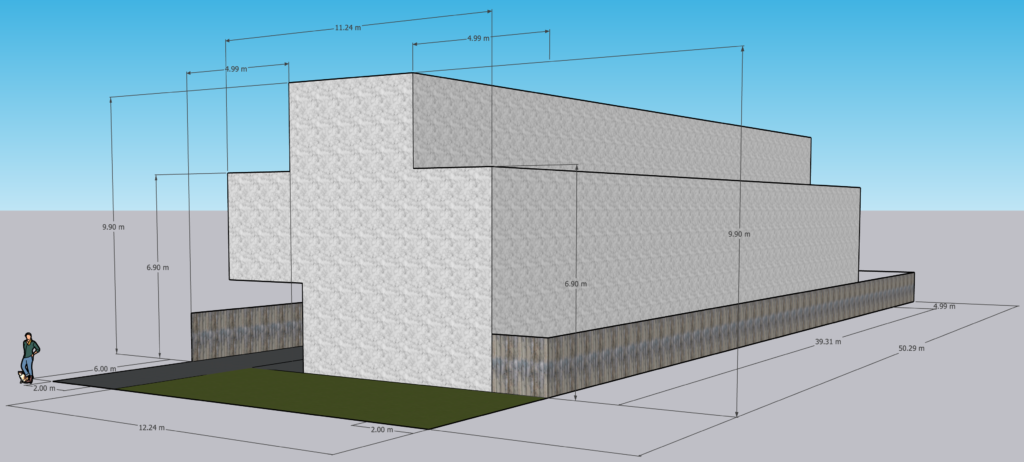

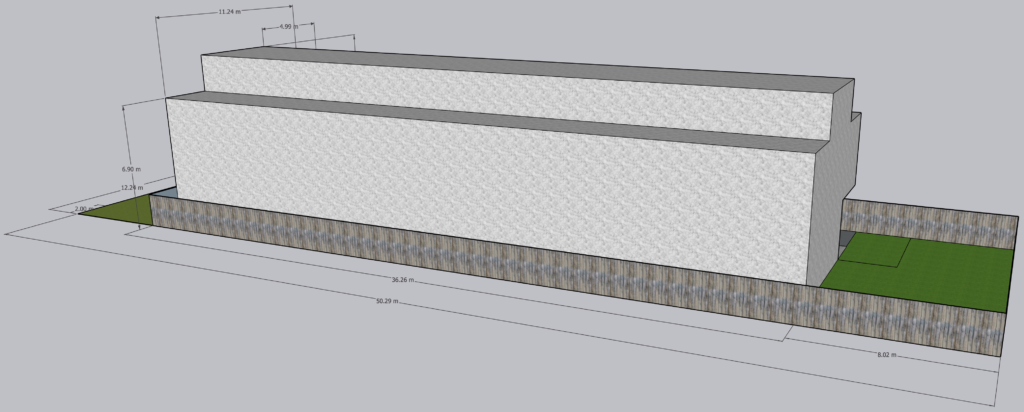

Neighbourhood Residential Zone

The Neighbourhood Residential Zone (the lower growth residential zone) has the same 35% Garden Area control as the General Residential Zone, so the building is the same length. Height comes down to a maximum of 9m. Note too it must be no more than two storeys, which isn’t clearly reflected in this drawing – this would likely reduce the prospects of building this form.

Thoughts

I have already editorialised more than I intended to about the merits of this change in this post. My intention here, really, was to make this exercise available so that people could get their head around what these standard-compliant buildings might look like. You can form you own views about whether this is encouraging good typologies, or reflecting the levels change intended in the zones. (I have written in some detail about what I think should be done with the medium density housing provisions in my book).

If you wish to play around with these drawings they can be downloaded here (Sketchup has a 30 day trial):

While I think these drawings make reasonable assumptions, there is room for debate about the way I have approached them. (While I have also checked them fairly carefully, it’s also possible I have made a mistake somewhere – there are a lot of moving parts in preparing these drawings while learning the software and making on-the-fly calculations.)

Ultimately, though, my version of these plans should not matter at all. This is an enormously consequential change. Whatever you think of it, surely the government should have produced some material showing what typologies and forms it thought the changes might lead to.