Note: the following article includes detailed spoilers for several Bond films and books, including the ending for both Casino Royale and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. You have been warned.

The exciting thing about the newest Bond film, Casino Royale, is that it starts the cinematic James Bond series afresh. There has been much commentary on what this means for the Bond series going forward, centring on speculation as to whether this change in tone will carry into the next film. What I haven’t seen a great deal of discussion about, however, is what the events of Casino Royale, and the associated rebooting of the series, means for our understanding of who Bond is.

This is odd, because it’s the “memory wipe” (for want of a better way to put it) that really distinguishes Casino Royale from its predecessors. There have been a number of times in the series where particularly over the top film (like Die Another Day) has been followed by a more down to earth one (like Casino Royale). It first happened in 1969 when the action-filled but romance based On Her Majesty’s Secret Service followed the hollowed-out-volcano epic You Only Live Twice. Since then, there was For Your Eyes Only after Moonraker, and The Living Daylights after A View to a Kill. In all these instances, the Bond series made a point of following a particularly silly entry with a movie closer to the tone of Fleming’s writing. But to actually throw out Bond’s history is a first, and creates a seismic shift in who we understand Bond to be, by changing the crucial romantic relationship in Bond’s life.

In most of the Bond novels, the women are not much less disposable than the smorgsbord of interchangeable women in the films. Yet there are two novels in which Bond’s romantic partner is much more important, and these become the relationships that define Bond’s character. The first is Casino Royale, the first Bond novel. In this, he falls in love with fellow agent Vesper Lynd during his recuperation from debilitating torture. At the time, Bond is disillusioned by his experience on the mission, suggesting to his colleague Mathis that the “heroes and villains keep changing parts” and that his service to his country has been fruitless. In this state of mind he decides he will marry Vesper, but before he can do so, he finds their relationship transformed as she becomes distracted and secretive. Vesper commits suicide, leaving a note explaining that she loves Bond but had been working as an agent for his enemies. The book ends with Bond’s heart turning cold:

He saw her now only as a spy. Their love and his grief were relegated to the boxroom of his mind. Later, perhaps they would be dragged out, dispassionately examined, and then bitterly thrust back, with other sentimental baggage he would rather forget. Now he could only think of her treachery to the Service and to her country and of the damage it had done. His professional mind was completely absorbed with the consequences – the covers which must have been blown over the years, the codes which the enemy must have broken, the secrets which must have leaked from the centre of the very section devoted to penetrating the Soviet Union.

The final words of the novel are spoken by Bond to his headquarters: “The bitch is dead now.”

It would not be until the tenth Bond novel, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, that Bond would again pursue the desire to marry one of his conquests. This time it is Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo (Tracy), the troubled daughter of organised crime boss Marc-Ange Draco. Bond and Tracy are married at the book’s conclusion, but as they drive away from the wedding, they are fired upon from another vehicle. Bond survives, but Tracy is killed: the book ends with Bond clutching her lifeless body to him. Once again Bond is penalised for letting his emotional guard down.

When the film series started, the rights to Casino Royale were divorced from those for the rest of the series. The films instead started with Dr No, the sixth novel, so Bond’s relationship with Vesper was never part of his backstory. In the early films Bond’s character is necessarily defined by Sean Connery’s demeanour, rather than the internal monologue Fleming could use in the books. This inevitably made him a less human character, and this effect only became more pronounced as Connery’s swagger increased and the scripts became progressively more flippant. When Bond sleeps with women in the early Bond films, it’s often to gain information: this becomes something of a thematic motif through the first five films, with a number of variations on the theme. At the same time, the sixties films have an overriding arc that sees the gradual revelation of SPECTRE, a crime organisation that is behind the villains of most of the early films.

These two strands build towards the film adaptation of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, which became the climax of the linked plots of the sixties Bond films. The film is a remarkably faithful adaptation of Fleming’s original, and is justly considered one of the best in the series. Bond’s relationship with Tracy is surprisingly touching, with Diana Rigg’s Tracy more than Bond’s equal. The wedding is shown, and the film ends exactly as the book does, with Tracy murdered by Blofeld and his partner Irma Bunt. George Lazenby has his one really strong scene as Bond as he sits, dazed, cradling Tracy’s head and kissing her fingertips. It’s a shocking moment, in which genuine emotion suddenly intrudes into a comic book fantasy, and it seemed to traumatise audiences. Critic Molly Haskell wrote in the Village Voice:

Their love, being too real, is killed by the conventions it defied. But they win the final victory by calling, unexpectedly, upon feeling. Some of the audience hissed, I was shattered.

Yet the Bond producers seemed to be spooked by what they had done. The next film, Diamonds are Forever, brought back Connery and set the jokey tone that would define the series in the Roger Moore era. More importantly, though, it simply ignored the events of the previous film: Bond is still chasing Blofeld, but the fact that he killed his wife is never mentioned. At one point Moneypenny flirts with Bond by suggesting he bring her a diamond attached to an engagement ring. As Jim Smith and Stephen Lavington put it in their book Bond Films: “Surprisingly Bond doesn’t respond by shouting, ‘My wife was murdered at the end of the last film you heartless cow!’ at her.”

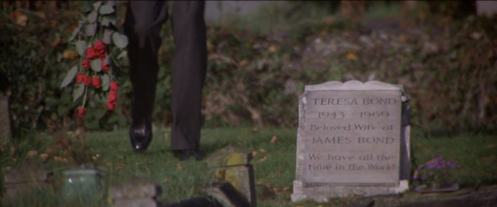

But Tracy’s memory would not be so easily suppressed. The fact that Bond had lost his wife hung like a cloud over the character, and Bond fans would cling to any mention of her. The loss of Tracy became the unstated motivation for any of Bond’s more sombre moments, and brief references to her were dotted through the films in the Roger Moore years. In The Spy Who Loved Me, Soviet agent Triple X starts telling Bond his own biography: she gets to his marriage and is cut off tersely by Bond. In For Your Eyes Only, Bond is shown in the opening sequence visiting Tracy’s grave. Of course, the same sequence then gives way to a silly action sequence in which Blofeld – Tracy’s killer – is offhandedly dropped from a helicopter down an industrial chimney. Nevertheless, the reference lingers over the film, which is unusually restrained by the standards of the Roger Moore films, and has led to readings of the film as a meditation upon Bond’s mortality and increasing age.

When Timothy Dalton took over the role in The Living Daylights, there was a feeling that the character was being “re-set” to some extent. A decisively younger actor was taking over the role, and the supporting part of Moneypenny was recast to a younger actress. Yet Bond’s history with Tracy didn’t disappear. If anything, Dalton’s gritted-teeth portrayal of Bond seemed more informed by his sorry history than ever before. The next film, Licence to Kill, confirmed this when Tracy was once again explicitly acknowledged, this time to explain Bond’s muted reaction at his friend Felix’s wedding: “He was married once… a long time ago,” Felix tells his new wife.

But that “long time” was getting longer, and by the time of the Pierce Brosnan films, the producers publicly questioned whether Bond could still be thought to have lost Tracy. The references to some sort of loss in Bond’s past started to get increasingly vague. In GoldenEye, the villain remarks to Bond:

I might as well ask if all those vodka martinis silence the screams of all the men you’ve killed… or if you’ve found forgiveness in the arms of all those willing women for the dead ones you failed to protect?

This could be a reference to anybody, and indeed the next two Bond films (Tomorrow Never Dies and The World is Not Enough), made half-hearted attempts to give Bond new women to mourn. But there was only one Tracy.

Which brings us back to Casino Royale. Now, for the first time, the screen Bond’s greatest heartbreak is Vesper Lynd, rather than Tracy. The subplot of Bond’s disenchantment with his job isn’t as pronounced, but certainly Vesper’s betrayal is seen to harden him: his definitive line from the book (“the bitch is dead”) is in the film, although it’s something of a throwaway. The whole point of the film is to define the new Bond, and – as in the early novels – that new definition centres on his relationship with Vesper. Casino Royale swaps a post-Tracy Bond for a post-Vesper Bond.

But the most intriguing question is this: has the re-boot given the producers to possibility of re-visiting the Tracy plotline, something akin to the way Batman Begins has given the producers of that series the opportunity to go back to the Joker? Casino Royale doesn’t wrap its plot up neatly, finishing with Bond picking up the trail of people above Le Chiffre (something he is able to do because of a last gesture by Vesper). It’s reminiscent of the way in which the early Bonds were structured, and it holds forth the hope that we might see a return to Bond films with some continuity of tone and plot from film to film. Enough time has passed since the early Bonds for new films to revisit the novels, and it would be wonderful to see a more Fleming-driven Bond series, one that built like the sixties films did to the great love, and tragedy, of Bond’s life. As good as the original On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is, I’d love to see a new version with a strong lead actor. Can the producers really let this new Bond carry on indefinitely without encountering Tracy again?

This essay was also published on CommanderBond.Net and at In Film Australia.