Prometheus (Ridley Scott, 2012)

Ridley Scott’s return to science fiction, thirty years after Blade Runner, would be a big deal on its own. That he has returned with a revisitation of the universe of his other science fiction classic, Alien, makes this an even more enticing prospect. Yet there’s a reason the trailers have soft-pedalled the connection to the 1979 film: Prometheus is quite a different film in both intent and execution.

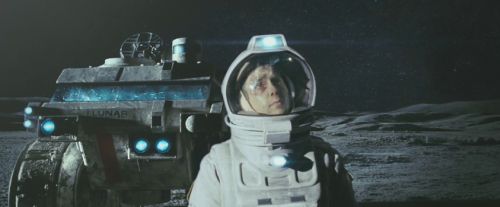

It takes place before Alien, and follows a deep space mission to find a star system that had been depicted in ancient cave paintings. Led by archaeologist Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace) and the improbably icy project sponsor Meredith Vickers (Charlize Theron), the mission hopes to uncover secrets about Earth’s origins. The team lands on a moon, finds and enters an ancient alien structure, and undertakes an orderly, well organised series of explorations in relative safety things start to go disastrously wrong.

Scott’s original Alien took a very similar opening set-up and turned it into a single-minded exercise in suspense and occasional visceral horror. Prometheus, commendably, is more ambitious. There’s a strong element of Alien-style menace, but Scott also wants to have a try at more thoughtful, idea-driven science-fiction. The film works to some extent on both fronts, but never really gels as a whole: it’s a film more interesting and laudable for what it attempts than what it actually manages.